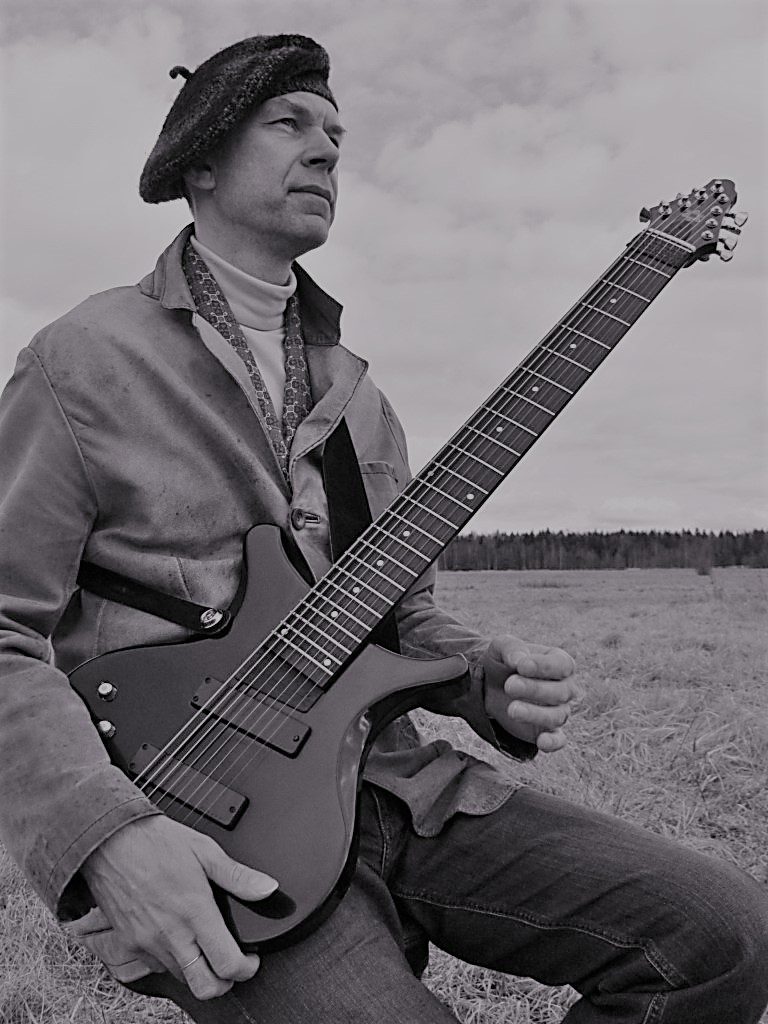

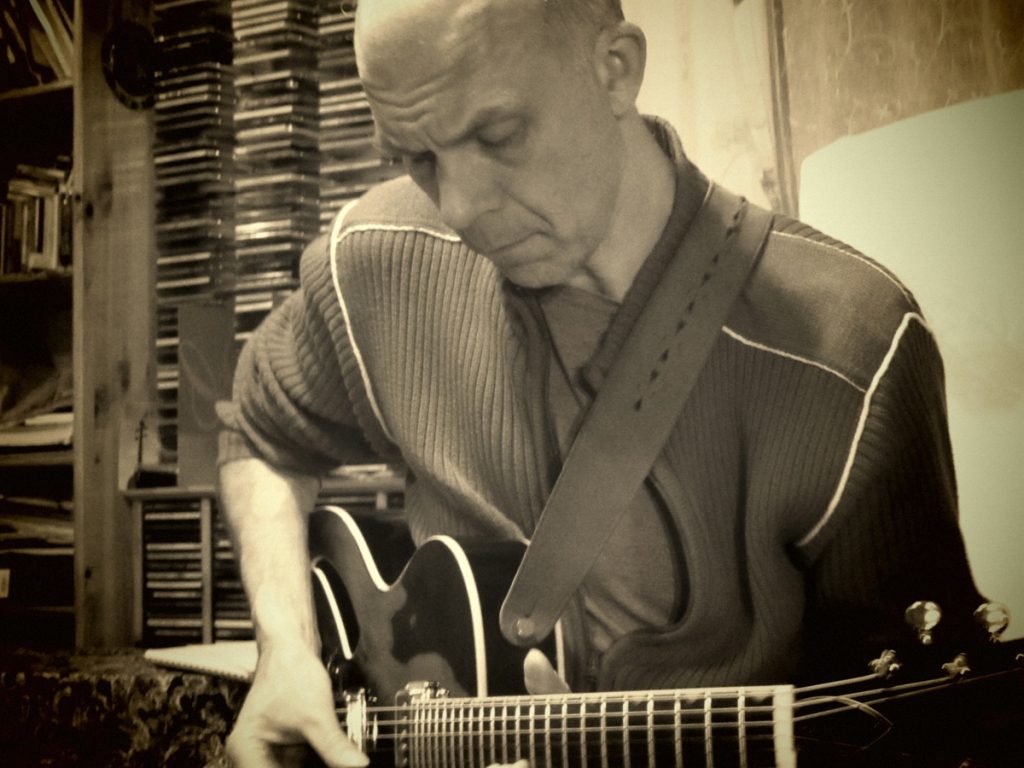

In 2016, the guitarist Robert Jürjendal was chosen as the Musician of the Year in Estonia. That alone tells about Robert’s exceptionally versatile approach to music making and of his highest professional attitude. Apart from the solo guitar and guitar ensembles he’s written music eg. for strings, harpsichord, brass and choir as well as for films, theatre productions and art exhibitions.

Robert’s career begun in the early 80s. Since then he’s been involved in an impressive number of projects, most of them quite well documented in the biography and the website. In this interview we do better by focusing on Robert’s art of guitaring, his relationship with technology, and with the rich music life of Estonia. And Inner would not be Inner if it didn’t try to deal with the issue of combining art and music.

The art of guitaring

The art of guitaring

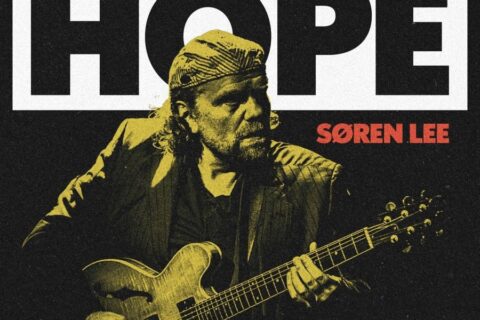

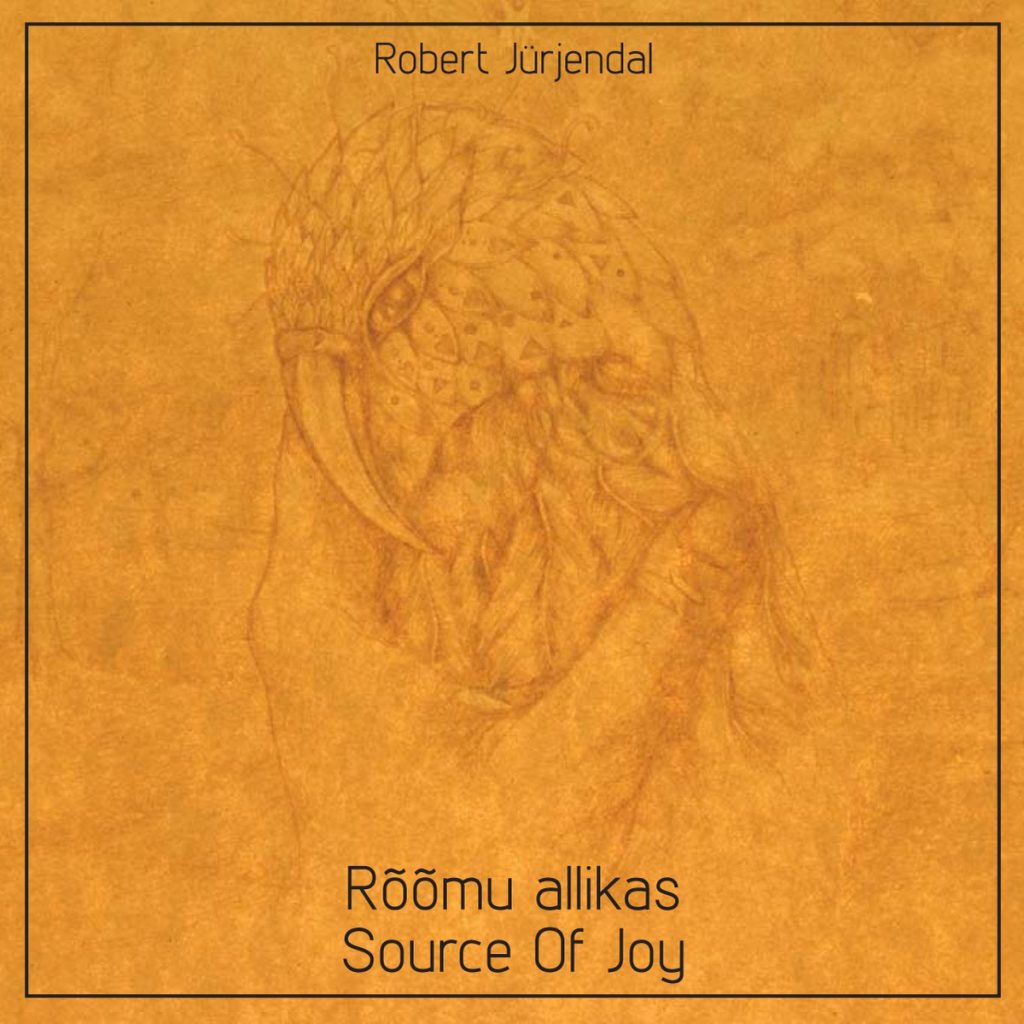

Aspiring to understand Robert’s music, and thoughts about music in general, we first posed 6 questions, based on Robert’s three latest albums: Source of Joy (2013), Balm of light (2015) and Simple past (2016):

Inner: The list of projects and groups you’ve with which you’ve been working is considerable. Working through projects looks like a natural and fruitful way for you to make, write and perform, music? Any risks?

Robert: Well, risk should belong to the art. Even if it sometimes hurts, it’s still a useful tool for getting experienced. Personally, it’s all related with an endless curiosity which has accompanied me almost last 30 years. I have had luck to work with an extraordinary and talented people – musicians, artists, writers, film makers, poets and poetesses, actors and actresses. Sometimes in these situations, the music is not always the first and most important thing, it may appear much later, but the essence of it is always present. The way how somebody thinks and acts has become for me more and more important.

Inner: You’re regarded as an ”experimental” guitarist and composer. The term (experimentalism) is often used fairly loosely. How would you yourself describe your experimentalism? Listening to your recent albums suggests that you’re not striving for a complete break with the past and tradition, but rather seek an extension of the use of conventional means?

Robert: Yes, I agree. In certain situations these terms and definitions tend to loose their original meanings. There have been some longer periods in my life when I seriously tried to be an “experimental” musician, putting myself to opposite of the mainstream world. But it went over very soon because I recognised that I was not able to express myself through the “experimentalism” as much as I wished. Terms like “flexibility and sensitivity” became much more important. The other question is an inspiration – I have noticed that this comes often from unexpected sources. Of course, some of these sources are experimental, some are not, some are hanging between, and some are absolutely simple things but with a new meaning.

Inner: Somebody described your guitar playing to me by saying that it doesn’t sound as if you were playing a guitar at all. Based on the 3 albums I’ve heard I’m inclined to agree, but are you? And if so, what possibly explains the impression?

Inner: Somebody described your guitar playing to me by saying that it doesn’t sound as if you were playing a guitar at all. Based on the 3 albums I’ve heard I’m inclined to agree, but are you? And if so, what possibly explains the impression?

Robert: The guitar is a fantastic instrument with thousands of possibilities. But there are certain limitations in the sound which you may not like if you approach music from a wider perspective. In other words, if the traditional guitar would be able to express all kinds of musical impressions there would’t be more instruments around! This is why I chose the electric guitar. I don’t know any other instrument with such a rich pallette of sounds as the electric guitar. There are so many ways how to make dramatic changes in one’s sound: a type or model of the guitar, the pickups, strings, picking style, picks, fingers (using nails or not), slide, bow, Ebow, capos, tunings – I use 2-3 different – vol. pedal, effects, amps, PA and so and forth. The combination of these things allow one to sound sometimes like a violin, choir, flute, bells or something abstract. But as you see, this is a view of a composer. One half of me is a composer, the second half is a guitarist.

Inner: Could the special quality of your music and playing style reduce down to looping? Or some other technology enabled effect? And if so, how have your ideas about looping changed over the years?

Robert: Looking back to the 90’s I was probably one of the first looping guitarist in Estonia. Everything felt new and interesting. I used the original Lexicon Jamman with an upgraded memory of 32 seconds and it was alot of fun. I did’t use a midi … I still don’t … and the result was more or less rhytmically accurate. But it felt as being part of improvisation, and I liked the idea of the possible “mistake”. Today the market is full of all kind of loopers and looping guitarists. There are artists who use pre-programmed looper software for special ambiet textures and compositions. Looping is just one way of making music, and there are many subtler ways of how to use the technology in a creative way.

It’s also very different if you listen to a looping guitarist from an audio recording or when you experience such an artist in a live performance. Personally I don’ t like the images where the performing musician is constantly staring at his or her mac on the stage. There are many jokes about this … Simply put, in that kind of situation the musician takes a passive and the computer an active role. My rule of the looping technique is this: whatever you do, do it in a creative way. It’s a little similar with using the delay effect – it should be not just repeating a note or notes but be part of the complex compositional technique.

Inner: Is looping an endless source of creation or does its potential, after a certain time, get limited?

Robert: If there are possible limitations, I’m not afraid of them, because I think we are all limited in a certain way. Nice if you can make your limitations enjoyable!

Inner: You’ve got a background in classic/art music. In the hindsight, what was it that dragged you away from it? An inner need to be able to improvise? What’s your stand on the topic of improvisation versus written music?

Robert: It’s all very personal. When I was young I used to listen to all kind of music. My father had a solid Soviet vinyl collection, mostly Latin music from South-America. When I was a teenager my mother took me to local music school to study classical guitar. Of course I was happy because the guitar was a very popular instrument. It all went well, but then in one moment I realized that I didn’t have a clear idea about my future music making, no clear goal. The picture, being a classical guitar soloist, didn’t match very well with my dreams. Years later, my interest turned more and more toward composition, guitar and electronics, and of course, into improvisation and sound innovation. In the late 80’s, I started to record my first improvisational compositions at Estonian Radio Studios. I would say it was more like live-composing than just pure improvisation. Even though all the parts of the music were improvised, the final thing sounded like “written” music. I think this is the kind of method I have been using years and years after. I like the idea of improvisation but what I don’t like is if the music, to the listeners, sounds too accidental. There are many composers who are used to perform their own music. And if there is a place for improvisation, it’s mostly naturally connected with the composition. But if you “write” the improvisation into a composition performed by other players, you have to be careful not to damage the composition. I think that improvisation requires an unconstrained, natural situation. The question is not between improvisation versus written music. They both have their own qualities, which sometimes belong together, sometimes not. I like the idea of uniqueness – I believe that there are artists/composers/improvisers whose style, sound and the way they improvise is so unique that nobody else is able to do this on a same level.

Inner: We’ve got here a radio program called Space debris. On Sunday evenings, for more than 30 years now, it has broadcasted all sorts of music from ambient to various electronic to what could be classified as sound art rather than music. Texture-based minimalistic material with a certain ethereal essence. Do you recognize your music from this description?

Robert: This what you describe always relates to a quality. I remember I had a gift card of the “Magical crystal room”. I decided to see how it works. Everything was nice and fine … except the music. I really tried to relax but it was impossible because the same disc with poor synth sounds with some ocean murmurs samples made me rather anxious than relaxed. This is what happens if the music is produced without an intension and clear direction. It can be fine for some minutes but probably not much longer. Times back when Brian Eno presented the ambient music, things were done in a different way. It was interesting to follow the sounds – they carried the listener into the unexpected world or caused some sort of feeling one never had had before when listening to “ordinary” music. In my own music I use quite often the texture based minimal sounds as a part of a bigger composition. Sometimes these sounds are hidden, sometimes they gradually turn into more powerful textures. For example, I used this type of construction in my piece Balm of Light from the second solo album Balm of Light.

Inner: Experimentalism, atypical sonics, improvisation, looping, effects, etc. – are just some points in the effort to understand what’s going into your music. How would you answer if someone asked: what to listen to when one sets out to listen to your music?

Robert: My music is strongly related with the use of the guitar. I don’t know, but maybe it makes sense to think that almost all sounds which I have produced are generated with the different guitars: classical guitar, 12th string, Gretch electric, Ovation seniacoustic, 8 Touch Guitar, Steinberger Spirit etc. One may think that something sounds just as an organ but its not – its just a guitar played with Ebow and modified with some Electro Harmonix effects. I’m always interested in producing new sounds, even it feels impossible in our so overproduced world. Also, it’s good to know that all my albums are based on the certain personal experiences and periods of my life. The titles are never accidental, their task is to introduce the listeners a certain theme.

Technology

Inner: Practically taking, all your recent music is to a large extent technology-tied. But on a more ”philosophical” level, how do you see the relationship between ”music and technology”? Technology is, of course, increasingly being integrated into all sorts of music nowadays, has been for last 70 years, classic included. Nevertheless, it seems that it’s not entirely incorrect to say that the practice has not fully matured: in particular as regards classic/art music, the integration often sounds clumsy and artificial. Also, purely acoustic music still very effectively resists the trend. In your mind, how would a fruitful marriage of technology and music sound? Or do we see disintegration of technology-based music from the purely acoustic one?

Robert: Combining music and technology has developed to a high level, but there is one thing we have to deal with consistently: the acoustics. Even using a very high quality sound system, the musical result can be very poor. The problem is that composers / performers often don’t think about the rooms where their new compositions are planned to sound. Is it a dry black box? Or a noisy club? Street? A small church or big cathedral? Or just a “normal” concert hall? These venues have all their own specific sound properties, some have creepy highs, some have 10 seconds echo, some have a lot of muddy mid frequencies, some have a short delay and so on. For me its so strange why these aspects are often forgotten or just ignored. Years ago I discovered that my electronic, especially electro-acoustical music sounds much better in a big church hall. The reason is simple: thanks to the church construction, and a long and soft echo, the digital sounds tend to loose their recognizable sharp structure, and start to blend with the acoustic sounds. And this is nice!

As regards purely acoustic music, yes, it will always keep its place in society because “it” knows how, when and where to sound. And people like things, which are natural to their ears. But as I said, the wrong use of technology and acoustics can turn even here things upside down. There’s much to study I guess.

Inner: I found the below on the net. Is it still valid?

”His main guitar is an Ovation semi acoustic steel guitar equipped with a MIDI pickup that he uses with a Roland VG-8 guitar processor. He also uses this processor with a Breedlove C15 Custom semi-acoustic guitar. In addition to these guitars and processor, Robert also uses several guitar effects and pedals. In the interview he revealed that he uses an E-bow, Electro Harmonix HOG, Roland Space Echo, and a Boss RC50 Loop Station. In addition to these effects, Robert also uses a Neunaber Audio Effects Wet reverb and is currently listed as an endorsed artist on their website.”

Robert: Ahaa … it’s valid but not a 100%. I develop my setup all the time. I have replaced my old Roland Vg8 with a Roland GR55 guitar synth. This is combined with my other engine, a POD HD500X, and with various specific effects as Neunaber Wet Reverb and so on.

Estonian music life

Inner: I just read from somewhere that more than 1000 concerts, smaller and bigger ones, are given every year in Estonia. I’m not sure if the figure covers the whole music scene, or just the more ”serious” one. As a composer and musician who has embraced a number of different genres – classic, jazz, electronic, progressive rock, sound art – how would you assess the state of the current music life in Estonia?

Robert: We have quite good times now because people spend more time and money to the different musical activities. But still, Estonia is a very small country with a small music market. Maybe this is the reason why I have shared myself through these years between different musical disciplines. For me it has been almost impossible to stay in one place doing just one thing here. I’m mostly using simultaneously two directions: composing, film and theatre music, and performing. There are times which are better for composing, and those which are better for performing. Some things are planned to take place in the future, some works have to be ready by tomorrow. Just recently I finished a score for a short film, had a premiere, and recording of my Missa Brevis for Girls Choir, el. guitar and percussion. Right now I’m completing an album of my semi-acoustic chamber music for the Danish/Estonian group Five Seasons, writing a music for a theatre play KALEVIPOEG and providing performances with Weekend Guitar Trio and with other artists. I’m waiting also for the release of a new album in the end of January by Colin Edwin (Porcupine Tree, Ex-Wise Heads, O.r.K. ) and me.

Inner: Assuming it makes sense at all, to what extent would you credit your Estonian background – music and culture – for the choices you’d made in your music?

Robert: We have a rich culture but we need to work constantly with this fragile thing. And this means working with the memory, because if we loose it, we are not able later to put together different parts of our culture. Our history is multi-layered as the country has been ruled by kings of Denmark, Sweden etc. There are still quite many empty uninhabited regions in Estonia. I think the emptiness, forests, silence and direct contact with the nature are things in Estonia which have a very big influence over me. I used to live and work in the countryside, close to the forests and bogs. Maybe this all can be found somehow in my music, its hard to say …

Inner: The claim is often made that every Estonian composers and music maker, independently of the genre, owes to A. Pärt in one way or another. From the parade ground, how would you judge the claim?

Robert: Its hard to overestimate what Arvo Pärt has given to Estonia, and to the rest of the world. For years he has been also the most performed composer in the world. He is honored by musicians and composers from different genres – from pop to contemporary, classical, and this is phenomenal. But otherwise, I appreciate also the music of Erkki-Sven Tüür, his works are wonderful. Erkki’s career started in a prog group In Spe, which was one of my favourite Estonian bands in the 80s.

Music and (fine) art

Music and (fine) art

Inner: Fragile (1997 – 2008) was your project together with Arvo Urb and an Estonian artist Tõnu Talve. It reads: ”The aim was to create real time show based on improvisational music and painting.” Could you tell us more about this project, and elaborate on the subject of ”fine art & music”?

Robert: Usually artists prefer to work in their own studio, which is more or less separated from the outside world. Actually, there are also musicians who do the same – they are able to produce nice studio stuff but you don’t see them performing on the stage. With the Fragile we tried to put together the energy of live art making and live music performance. For us, musicians, it was a natural matter of musical improvisation. For Tõnu, as an artist, it was something very special. He used enormous energy to get the result, which was a completed painting. The music was mostly based on long guitar loops with hard drumming – it sounded loud and psychedelic, even shamanistic. We released three albums, which where completely different, but with the same amount of energy. These were crazy times..

But my connection with the fine arts is still active. Some years ago I begun to organize a SOOLO (solo) music performance series at Tallinn Art Hall. Since that time many interesting solo performances have occurred. This year a Finnish cello player and composer Juho Laitinen is coming to perform there.

Inner: Thank you so much, Robert, for the interview!