I find it quite astonishing how the reception of baroque concertos has undergone a major change in past two decades. Think of Vivaldi’s concertos (the 300 recordings of the Four Seasons, for example). What’s left from the 1980s? The melodic solo violin in front of the smooth sounding string orchestra? Loud instruments? Bland tempos? Et cetera. No. Instead, more freedom, more spontaneity, more improvisation. Performances that are a way more faithful to the music’s energetic nature. Plus the rough, rastling and fast sound of the period instruments.

Inventive, playful, sparkling. That’s what the Four Seasons is about, and that also applies to other concertos from the period when the genre was born, first in Italy and then spreading elsewhere in Europe, France and Germany especially.

Delightfully many contemporary baroque orchestras seem to have realized the electricity and pulse that the baroque composers loaded onto their early concertos for small string orchestras. One that certainly has is the Finnish Baroque Orchestra, FIBO in short.

In a recent concert they gave a good go to Telemann (Overture series), Fasch (Symphony, A minor), Vivaldi (Concerto for strings, G minor), Veracini (Overture series) and Bach (the second Brandenburg concerto). What a swing, punch and flow!

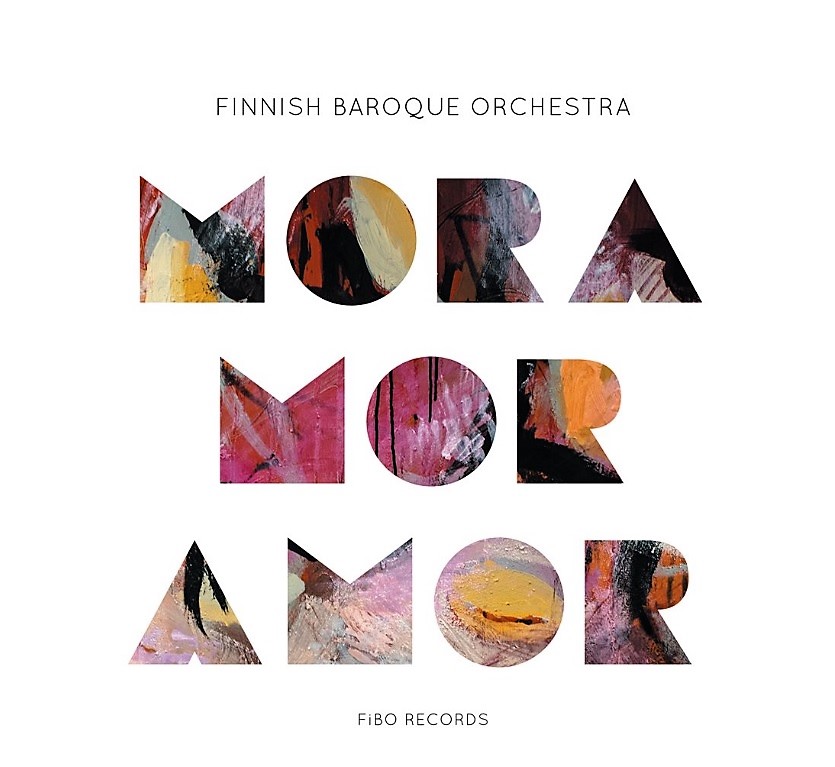

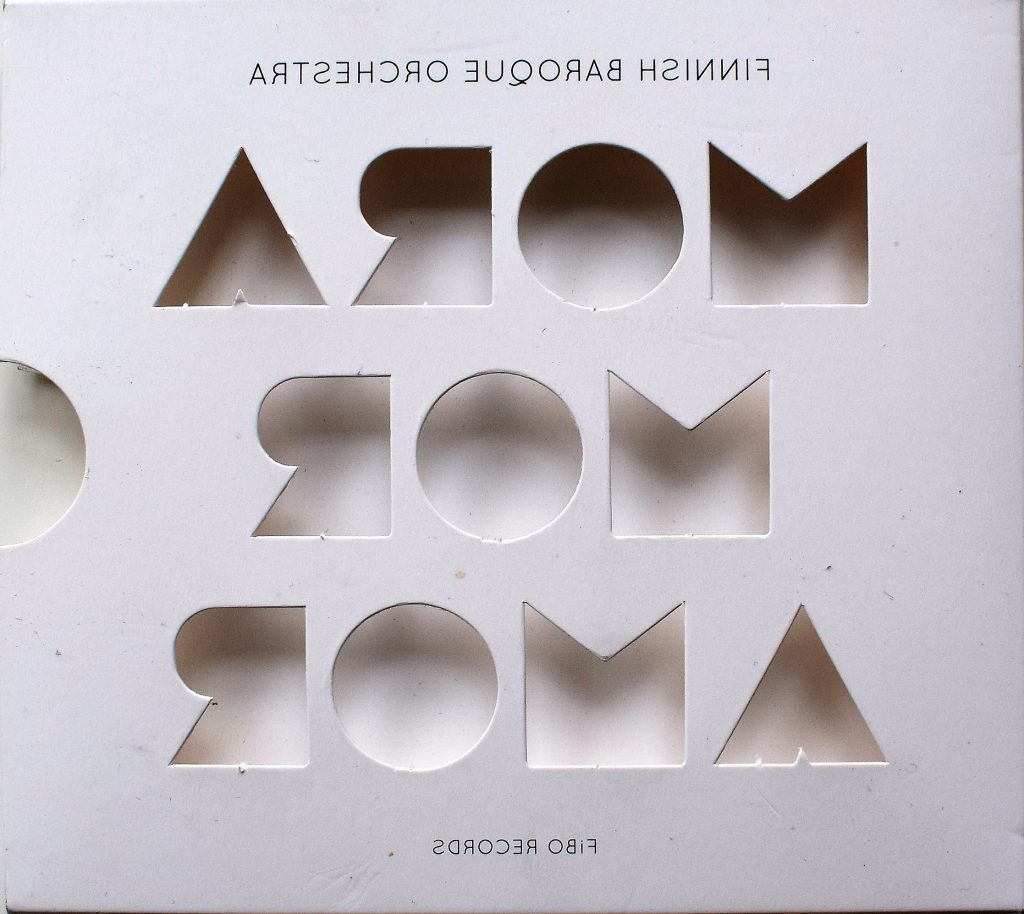

The FIBO’s unique ”touch”, the temperament, is discernible, through the loudspeakers, on their very first album MORAMORAMOR (featuring two Vivaldi’s Concertos, and two of Bach’s five Brandenburg Concertos – No 3 and No 5) but unfortunately to the lesser extent than live. Too bad for the HiFi enthusiasts – and recording engineers – but face to face the impact is much more vigorous.

New music for a baroque orchestra

The topic of today is not, however, baroque music/concertos, but contemporary baroque music! Or perhaps more appropriately: new music written for a baroque orchestra. Not too many composers cultivate and do it but some do. An advocate and genius of the genre is indisputably the Finnish composer Jukka Tiensuu.

Tiensuu is well placed in composing ”modern” baroque music. First off, he is known to be a generalist in the best sense of the word: hence, the versatility and diversity of his works (aleatoric, serialist, electronic). Second, he doesn’t shun making use of improvisation, and experimenting eg. with microintervals and extra-musical elements. Finally, being a harpsichordist himself, he is keen on ”keeping up a constant dialogue with the past”.

An enlightening intro to Tiensuu’s music for a contemporary baroque orchestra is Brandi, a piece Tiensuu wrote to replace the 2nd part of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No 3. Bach famously wrote the 2nd part just as a sequence of two chords, and it is later thought that he thereby gave the musicians a chance to improvise a cadenza of some sort. In Brandi Tiensuu takes the bull by its horns and presents his idea of how such cadenza might sound employing the same line-up of instruments as in the original. And how finely and tastefully he does it! With a delicious startlingness, sophistication and style. The listener is not left to ignorance as to from which period the music comes, and yet the piece, music, so seamlessly integrates as the middle part of the Concerto, to such a degree that it’s not impossible to imagine that some musician of Bach’s time, some wise guy, could have suggested a similar cadenza.

Tiensuu’s other modern baroque piece is Mora, a 19 minutes long vocal concerto written for a “Baroque orchestra and Baroque aesthetics”. Tiensuu would not be Tiensuu if the voice (tenor Topi Lehtipuu) were what we would think it were in vocal music. Instead, it’s treated as a flexible instrument making all kinds of sounds including meaningless speech, laughter etc. The tenor imitates the sounds of the instruments, and the orchestra answers.

Tiensuu’s other modern baroque piece is Mora, a 19 minutes long vocal concerto written for a “Baroque orchestra and Baroque aesthetics”. Tiensuu would not be Tiensuu if the voice (tenor Topi Lehtipuu) were what we would think it were in vocal music. Instead, it’s treated as a flexible instrument making all kinds of sounds including meaningless speech, laughter etc. The tenor imitates the sounds of the instruments, and the orchestra answers.

Curiously, if Mora were a piece of contemporary music with modern aesthetics (whatever that means), it could be off-putting or at least contain some disagreeable elements. In the context of baroque aesthetics all seem to be musically well-grounded and fitting. As an example of Tiensuu’s effects: in the second part (Voiku) he makes a tuning break become part of the whole composition. He also makes good use of the fresh sounds born by playing period instruments using modern playing techniques; and so forth. Some of these effects in Mora made me laugh, some other, eg. how he makes the cello or double bass sound, made me humbly impressed.

Much for the same reasons I was truly fascinated by Tiensuu’s composition Innuo, which has not been recorded yet but which Fibo performed in the concert. Oh, that pulsating and thrilling tension right from the beginning between the modern composition and the Baroque orchestra, followed by characteristic sensitive chords and clever themes. On top of the musical fabric clinking and chirping sounds of the recorder and violin sparkle like a mountain brook but then are suddenly interrupted by hypnotic rhythmic steps. It’s new and it’s insightful. It’s humorous.

No name, no linear notes

No name, no linear notes

Innuo doesn’t mean anything. Nor does Mora. Vaiko, Volku and Raiku, the three parts of Mora, mean nothing. Tiensuu is a composer, not a writer. He operates with abstract components void of meaning, not with words. He stopped commenting on his works already in the 1980s. No liner notes, no interviews. He prefers to let his musical contribution speak for itself. He writes music but does not write about his music. He’s not relevant, his music is.

By doing this he touches one central question of philosophy of aesthetics: the role and relevance of ”authorship” to the meaning or interpretation of a work of art. On one view, it is the pure ”language” which speaks and determine and expose the meaning, not the author. On this view, the written text/composition is a mere collection of influences from a multitude of traditions and cultures, and never originating just from the author. The author’s perspective can be disregarded, and the explanation and meaning of a work, its interpretation, need not be sought in the ”psyche, culture, tastes, passions, vices of the author”.

Another school of thought thinks contra-wise – any knowledge of the author/composer including his or her commentary, adds to understanding the true meaning of the text or work of art.

As far as music is concerned I suppose Tiensuu is an advocate of the former view. Music simply cannot convey meanings in the ordinary sense (ie. other than musical ones as Eduard Hanslick put it) and thus any attempt to explain and verbalize music is deemed to fail. Surely, the composer may have ideas on how his or her music is to be performed, but that’s another thing. What shows that Tiensuu is more interested in the music than the person or people who wrote it, is that he is known to be keen on the world of music as a whole, exploring cultures, listening, performing, and ”having a curious fascination for the unknown”.

”He travels all roads, acknowledges no taboos, is interested in and eruditely aware of what others have done”, writes one commentator.