Just recently I stumbled into two articles that deal with European colonialism and its cultural ramifications. One was “Savagery” and “Civilization”: Dutch Brazil in the Kunst- and Wunderkammer by Virginie Spenlé (JHNA 3:2, Winter 2011); and the other “Zwarte Piet and Cultural Aphasia in the Netherlands” by John Helsloot (Quotidian, 2012).

As to the first, Spenlé shows how iconography of carved coconut cups from Dutch Brazil was used, in this case by Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, to suggest how “savage” Brazil was “civilized” under the peaceful leadership of the Protestant count”, but that when the objects were integrated into a different context, eg. art collection, they underwent a connotational paradigm shift to be regarded later as an objective illustration of Brazilian natural history.

The second article by Helsloot focuses on the cultural inability of Western societies to recognize (use the right words, pay attention to, avoid disregard) its colonial past and its racist practices, in this case related to Zwarte Piet ritual in the Netherlands (blackfaced character acting as the server of the master Sinterklaas). In considering what results in this failure (aphasia) to connect the white master’s cheerful black servants with the events in history that were so gruesome for people of African descent, frequently leading to their deaths, Holsloot goes through several options including the failure, due to low degree of reflexivity in ritual, to see the more complicated message beyond simple representation producing secondary non-racist explanations. Black people see Zwarte Piet differently because they identify with Zwarte Piet, reflecting their own status in Dutch society being in a second-rate position just like Zwarte Piet in the Sinterklaas story.

This all came back to my mind when I saw, at the EMMA Museum, a video work by a Danish-Trinidadian visual artist, Jeannette Ehlers (b. 1973) who’s known for addressing issues of memory, structures of racism, and colonialism by utilizing her own body and image manipulation in her works. For example, in her performance Into the dark Ehlers, taking H.C. Andersen’s play The Mulatto (1840) as her starting point, asks: What does it mean to be the inheritor of colonial history? The work then unfolds an expansive legacy of Black anti-colonial resistance through a poetic, fragmented series of scenes and soundscapes paying tribute to renowned writer James Baldwin, founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as labour revolt leader Queen Mary, for whom Ehlers, together with La Vaughn Belle of the US Virgin Islands, created the first sculpture to memorialize Denmark’s colonial impact in the Caribbean and to celebrate those who fought against it.

The 7m high sculpture named I am queen Mary was placed in front of the West Indian warehouse in Copenhagen, and it’s the first monument to a Black woman in Denmark. The figure is said to be an allegorical portrait of Mary Thomas, a sugarcane plantation worker who was one of the “Queens” of the largest revolts in 1878, in which fifty plantations and most of the town were burned in protest.

Black bullets

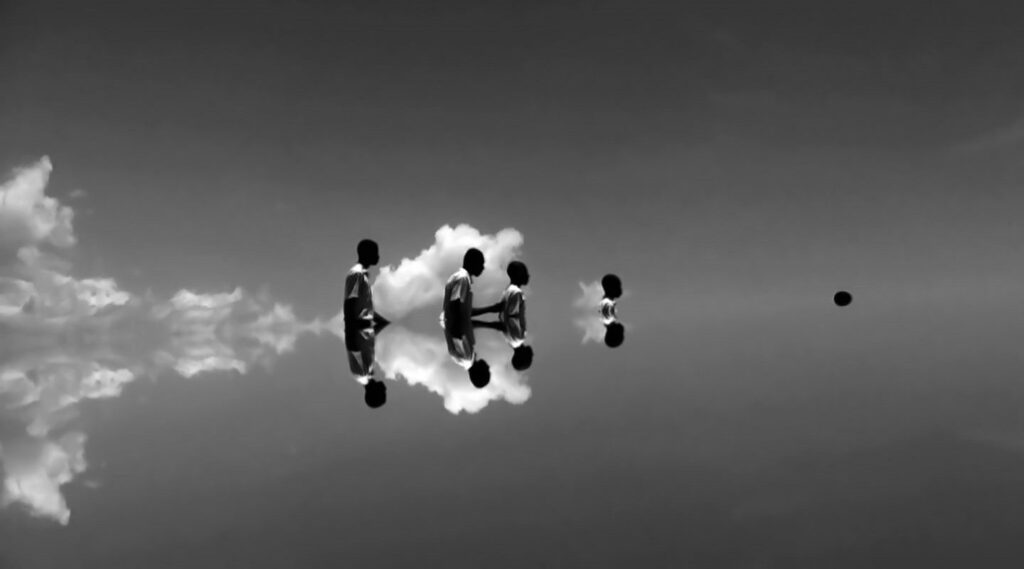

Black Bullets is an homage to the Haitian revolution of 1791 when enslaved Africans rebelled against the French colonial rule and slavery, known as one of the cruelest periods of forced labour. The Haitian revolution, the only successful slave uprising in history, set the scene for Haiti’s independence in 1804.

On the video, walking human figures and their reflections are depicted against the sky on a mountain-top fort, which was built by the first black Haitian monarch Henri Christophe at the start of the 19th century to defend independent Haiti against the French. With the video piece Ehlers again reminds us that history is not the past: colonialism still influences power and resource distribution around the globe, the Nordic countries included.

It’s good to stop and give that a thought in front of a big video screen.

Jeannette Ehlers

1973 Denmark

Black Bullets, 2012, video, 5 min, Recorded at The Citadel, Haiti, Sound: Trevor Mathison, Technical assistance: Markus von Platen, Camera: Jette Ellgaard & Jeannette Ehlers.

The video work is on display until 14th August 2022.