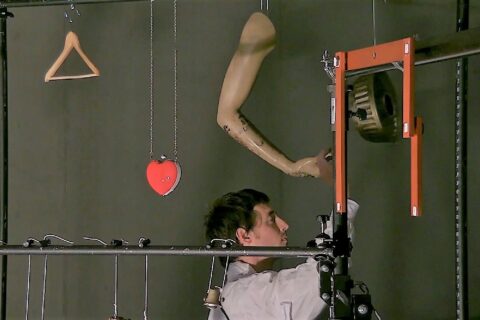

The opening image: Ugo Rondinone 1964, Brunnen, Schweiz, ‘I don’t live here anymore’

Men like to reason about technology. But scratch the surface a bit and you’ll see that the masculine attitude towards technology is anything but rational, and often highly emotional instead, going far beyond simple instrumental use of technology.

Think of gear/engine romanticism, for example (I’m following here one of the few philosophers who have touched the issue *). Such romanticims is active and optimistic in nature, and typically sticks to some outer features (how something looks) of technology or to experiencing technology as such, and in both cases is dramatic enough to attract emotional reactions. Gear/engine romanticism can manifest itself as a permanent attitude toward certain class of equipment/gear but also be rhapsodic: an instant fascination about some specific technical feature, often combined with the heightened feelings of nostalgia.

This kind of emotionalism that clearly exceeds the simple use of technology, is something very masculine in nature (women often just care about whether the device works or not, and if it does, forget it), and is often directed to objects such as cars and Hi-Fi, preferably very rare and very expensive. The emotion can grow hysteric and be erotic.

There are two ways to look at this technology-induced masculine infatuation and rhapsody: according to one, such emotions are real and peculiar, pure and strong, not just immature projection and supression. A child is not able to feel this sort of emotion, women seem to be indifferent.

On the other hand, the masculine emotinal attitude toward technology (understood as the realm of technological devices and objects) can be conceived as trivial infantilism, childishness, resulting eg. from emotional coldness and inability to express feelings. According to this view, the fact that an engine or gear can arouse so many strong emotions in itself shows how men pass the reason and logic.

A somewhat milder interpretation would be to see the technology-related anti-intellectualism and the immature rhapsody, not infantile but atavistic, reversion to something ancient and ancestral. It is as if men have fallen in love with themselves as young boys and are looking for the authentic feeling of enchantment caused by technical toys.

In view of this all, there seems to be going on transformation from old-fashioned gear/engine romanticism of the last century to current masculine infantilism nourished by the game industry. In the 1970s or 80s, it would have been impossible and considered highly immature that a man in his thirties would introduced himself as a person who’s skateboarding and playing computer games.

Why aren’t women experiencing similar emotions about technical devices? Why does it appear to be so exclusively masculine? One possible answer is power. Men take the atavistic feeling of power, that technology seems to bestow them, as original and fundamental, somehow essential for masculinity. Feelings aren’t just the property of women, men do have them too but direct them differently. This male love for technology is so strong that men can probably feel it even if they recognize feministic features in themselves.

This is mind it was interesting to visit two recent art exhibitions both dealing with masculinity.

Dark side of masculinity

The first, Mend and Masculinity, was held last autumn in the East Wing of the Lousiana Art Museum, Copenhagen Denmark. The works put on display were from the Louisiana’s own collection, mainly pictures of people, and many of them men: Warhol, Antony Gormley, Ulay, Georg Baselitz, Ugo Rondinone and Francis Bacon.

According to the museum, the purpose of the exhibition was to show how masculinity has many faces:

”While numerous artists after World War II turned to an abstract vocabulary, others stayed with figuration, creating radical counter-images to war-propaganda depictions of strongmen, invincible soldiers and triumphant figures. This dichotomy runs through the collection. With existential angst and humour, self-deprecation and self-loathing, the works illuminated and punctured a number of cultural clichés about gender that used to be prominent and still figure in pop culture, as well as in political and military ideals.”

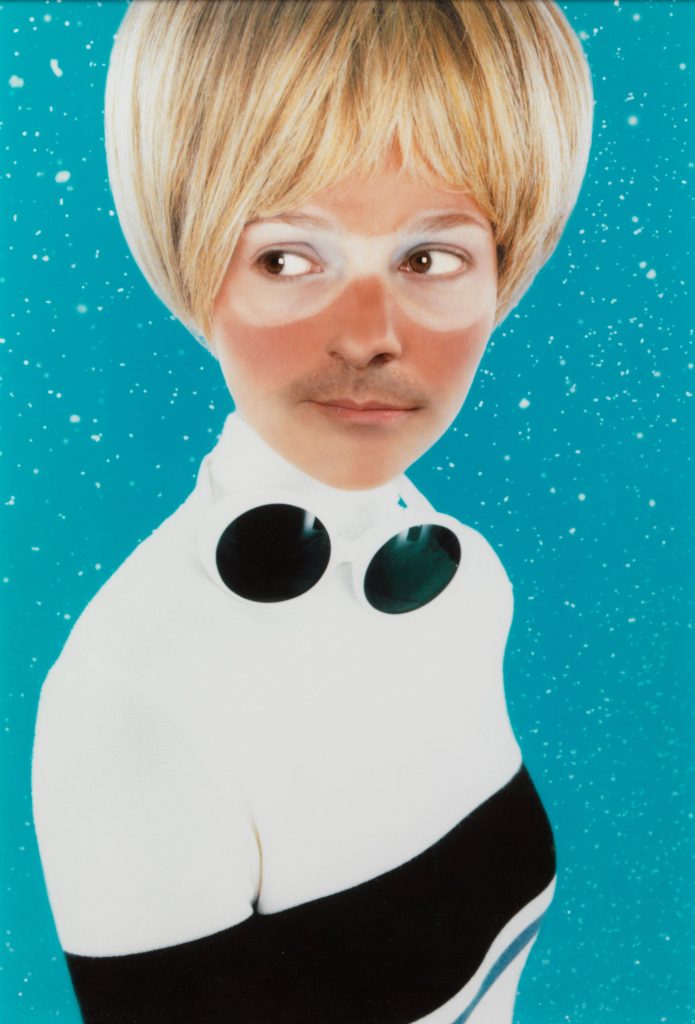

Many of the works were self-portraits, more or less distorted, apparently questioning the concept of the confident male artistic genius. It was clear that these artists were technological pessimists to say the least, not sharing the optimism of the futurists in the first half of the 20th century. But their pessimism wasn’t pastoral back-to-nature type of pessimism typical of romanticism but darker, much darker, and uncommunicative, self-centered and, well, mad. These artists weren’t too much interested in the surrounding society or environment, and just indifferent about the technological development, or so it seemed.

Metamorphoses of Masculinity

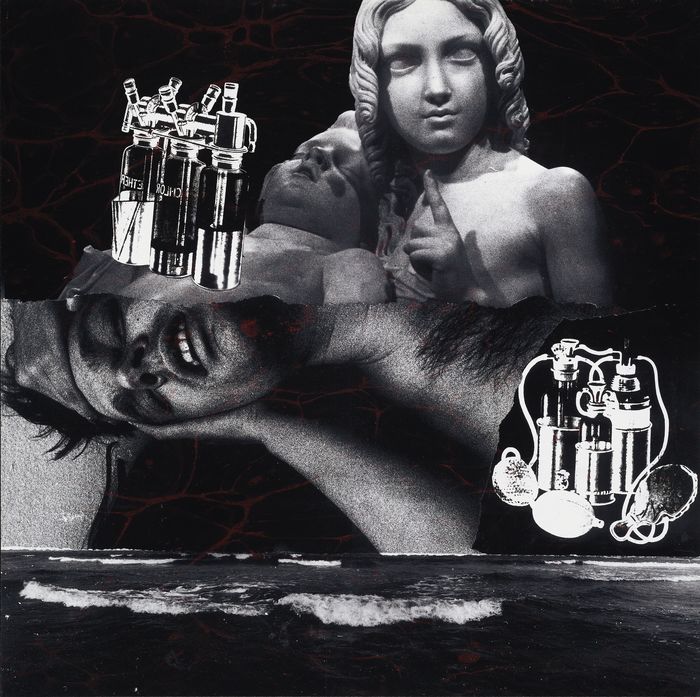

In this regard, the other exhibition, The X-Files (Registry of the Nineties), at the Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, Estonia, was entirely different. The exhibition was part of the Kumu Art Museum’s research project focusing on the 1990s.

Here’s the museum:

“The X-Files exhibition delve into the deeper layers of the decade and tries to shed light on works that have been overshadowed or forgotten or have even disappeared from the cultural memory. The exhibition also tries to accurately depict the societal metamorphoses that characterized this explosive decade, as they are reflected in the art found outside of canonical works.”

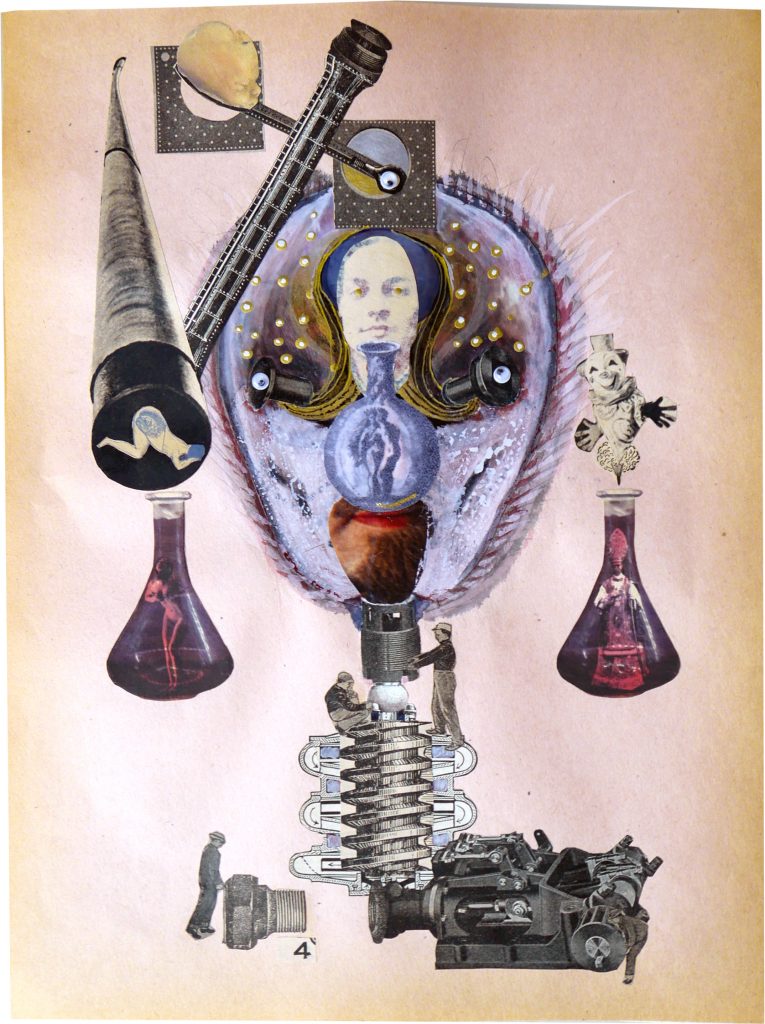

The exhibition was divided into eight abstract sections, with the following subtitles: ”Intro”, ”The Flow of Reality: Social Transformations I & II”, “Estonian Studies”, “Cyber Tower”, “Phenomenon: Commercial-Performance”, “Autompsyko Supervegos”, and “Metamorphoses of Masculinity”.

Narrowly speaking metamorphosis means a profound change in form from one stage to the next in the life history of an organism. More generally, metamorphosis is a complete change of form, structure, or substance (as transformation by magic) or it can refer to any complete change in appearance, character, circumstances, etc., or to a form resulting from any such change.

Unfortunately, it remained somewhat obscure how the works on display portrayed or exemplified the underlying idea of metamorphosis. Somehow the transformation displayed was more personal and individual than societal or historical.

Literature: Timo Airaksinen (The University of Helsinki), Tekniikan suuret kertomukset. Filosofinen raportti. (The Great Stories of Technology. A Philosophical Report.), 2003.