On September 29, 2016, the long-awaited moment: The new main building of the Estonian National Museum opened its doors in the Tartu Raadi manor estate, not far from the place where the museum operated between 1922 – 1944. At last the museum was given premises designed specifically for a museum!

The Estonian National Museum, the Eesti Rahva Muuseum, was founded in 1909. Around that time Estonia still belonged to the Tsars in Russia, commemorating the folk tradition of the storyteller Jakob Hurt (1839-1907), partly to preserve his collections.

The museum organized an acquisition of large collections of items between 1911 – 13. In 1922, a Finn Ilmari Manninen became the museum’s first professional director, and the then independent Estonian state handed over the Raadi manor as the museum’s main building. The previous owner of the manor, the family of von Liphardt had moved back to his homeland in Germany with fear of the Bolshevik Revolution, after which the state had taken over the manor.

The first exhibition of the museum was opened at the Raadi main building in seven rooms in 1923, and the museum’s permanent exhibition was opened in 1927, followed by the Finnish-Ugric exhibition year after. Collecting material from the people continued, and a communication network was set up. The museum operated on the same principle until the war years. The museum’s speciality was folk culture, especially in rural areas.

In 1940, the museum was renamed as the State Ethnographic Museum, Riiklik Etnograafiamuuseum, because in the Estonian Soviet Republik it was not possible that a national museum of its own could exist. According to the official ideology there was only the Soviet nation, no Estonian or other. The Russians burned the Raadi Manor in 1944 and took the area for military use: an airport was built there. The museum – the museum staff, the archives and the library – moved to an old courthouse by the Veski Street (Myllykatu). Only one small room was available for exhibitions.

Later the museum received two churches, the Church of Paul and St. Alexander Church, as the warehouse for its collections. Due to this maneuver, the exhibition and collection activities of the museum were constrained severely. The collections were also axed. The museum focused on research and begun to produce ethnographical films. One of the advantages of the Soviet era was the fact that field work among the Finno-Ugric peoples living in the Soviet Union could be made annually since 1965. In those years, the museum generated major collections of Finno-Ugric materials.

New Beginning: The National Museum name will be revived and the operation will normalize

The name Eesti Rahva Muuseum was reinstated during the glasnost in 1988. The collapse of the Soviet Union and Estonia’s New Independence in 1991 finally gave the museum the opportunity to normalize its activities. The most important thing was to ensure that the museum would get proper exhibition facilities. Those could not be placed in the existing main building, which is why another building had to be used. The former Kuperjanov street-club by the club house of railway workers, not too far from the museum’s main building, was selected. The building was named simply as Näitusemaja (exhibition house). A new permanent exhibition called Eesti. Maa, rahvas, kultuur (Estonia, the land, the people, culture) was opened in 1994. In the following twenty years numerous exhibitions were organised, and new exhibition and museum pedagogic solutions were introduced.

The idea to have a new museum building built in the Raadi, the museum’s original location, was first presented at the end of the 1980’s. In the so called “singing revolution”, around 1990, the museum that had taken back its old name ERM (Eesti Rahva Muuseum) became a key symbol for nationalism. The idea to return the museum back to Raadi inspired many Estonians, but promoting the matter proved to be difficult in practice.

In the beginning of the New independence, the idea was still maintained in some circles, but it was considered too utopian. At the same time there were other types of plans for the location of the new museum building: an architectural contest was arranged in 1993 where the museum would have situated in a site in central Tartu.

It was not until the beginning of the new millennium that the project to return the museum to the Raadi began to get off the ground. The decision to invest in the new main building on the Raadi plot was made in 2003. As early as 2000, the new warehouse building was being built. The 4000 m² warehouse was completed in 2004.

The museum’s new main building for the Raadi

Since the name of the National Museum was restored, the idea of a new Raadi museum was in the mind of many. Each of the museum’s managers Aleksei Peterson, Tõnis Lukas, Art Leete, Krista Aru, and again Tõnis Lukas promoted the matter during their period in office. When the Parliament Riigikogu in 1996 decided that the state would build the National Museum after the Academy of Music, and the State Art Museum, the plan was already on a firm footing. The final decision to build the museum in the Raadi estate in 2003, and the launch of the architectural competition in 2005 were the following important steps. The competition attracted 108 candidates, of which the winner the DGT Architects office (architects Dan Dorell, Lina Ghotmeh and Tsuyoshi Tane) was selected next year. The Estonian government decided to start the construction work in 2012, and the base stone was laid out in 2013.

In the fall of 2016, the Eesti Rahva Muuseum was finally ready to take over its new building and open the doors to the public. The opening ceremonies were held on 29.9.2016.

The keynote speakers were President Ilves and the museum director Lukas. Both speeches were rhetorically brilliant and no one was left unclear what sort of effort building the new museum had been. Great attention was also given to the museum’s opening ceremony (including a full-length live broadcast television show) by the media, and it was stressed that the museum was built with Estonian funds, and not with EU grants, for example.

The keynote speakers were President Ilves and the museum director Lukas. Both speeches were rhetorically brilliant and no one was left unclear what sort of effort building the new museum had been. Great attention was also given to the museum’s opening ceremony (including a full-length live broadcast television show) by the media, and it was stressed that the museum was built with Estonian funds, and not with EU grants, for example.

More images after the next section.

On the architecture

by Lars Tørressen architect mnal

After becoming independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, building a new National Museum was a good opportunity for Estonia to state its national heritage and uniqueness. It is against this background that the architecture of the new building must be understood.

The architects’ location plan for the new Estonian National Museum is a key to understand the position and shapes of the building. From a bird- eye-view, the intense graphic beauty of the interweaving of the soft landscape and airfield concrete is a staggering contrast to the history of the place, the Soviet military base and loss of the original museum in WW II.

By placing the new museum at the end of the runway and transforming it to a public space/roof the architects have turned the airbase into a new positive spatial meaning. The spatial generality of a functional slope at the end of a long free surface has the strength of openness to coming interpretations and programs.

The monumentality of the building is constituted of two qualities: the alignment to the runaway and the crystalline clarity of shapes, light and materiality. At this large scale the architecture succeeds, but at the human scale it suffers some; apart from the entrance, the scale of the building is out of proportion with the human body, our height, our own bodily dimensions. The entrance is spectacular, but the building does not define any spatial interaction with the surroundings where social activity is taken into consideration. Just plain walls – from the inside it is fine with glass, but from the outside glass is far from transparent.

In the history of architecture there has always been a hierarchy of dimensions in a building, a proportional subdivision, of facades, of spaces outside and inside, trying to connect the huge building scale to the size of the human body. Some modernists like Hertzberger in Europe and Louis Kahn in the US, are good examples, and later in a totally different architectural language the office Sanaa in Japan, for instance. All those have good examples of buildings made for human-sized people.

The challenge, in general, of the new museums of this scale, and it also applies to the new Norwegian National Museum in Oslo, is the balance between functionality as a museum, and the grade of spatial and structural interaction with the surrounding context, be that a city or a landscape. The building may simply be too big or too long to walk around.

More images

The sloping building on the runway of the former Soviet military airspace symbolizes the Estonian’s national independence and rising self-determination.

In front of the main entrance on the opening evening.

Altogether 2000 people came to celebrate the opening of the new museum.

Of all the permanent exhibitions of the museum, Kohtumised (encounters) presents the stages of Estonian people and their everyday life from prehistoric times to the present with a bold, open-minded approach. The Uuri kaja (Ural echoes) exhibition is based on the museum’s extensive Finno-Ugric collections. The exhibition area of the museum is nearly 6000 m². The electronic texts of exhibitions are readable by each visitor in the language marked in the personal visitor card.

The oldest part of the Kohtumised exhibition presents Kukruse emand, the grave of a housewife from a rich house from the turn of the 11th – 12th century, found in 2009. At the other end of the same space is book shelf from the Soviet era.

The ornamented wooden beer mugs are one of the main symbols of the Estonian peasant culture. Here’s the whole wall of them.

The visitor cannot mistake the museum for other than an ethnographic museum.

More collections.

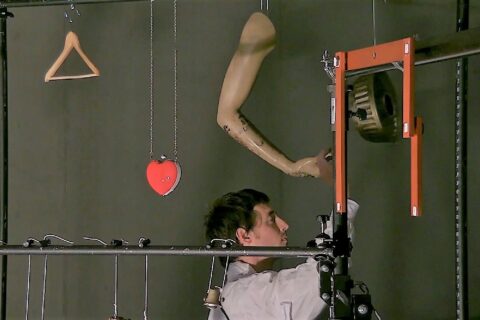

Wall mounted objects.

Windows on the floor give visual access to storage spaces underneath.

The museum also has a huge library.

On the long wall of the museum there’s a loading door from where large furniture and other museum items can be brought in.

Water is an essential element of the museum whole.

In the evening light.