A recorder can measure anything between 10 cm and 2 metres. The most popular is the C-tuned soprano recorder – the one that everybody knows from the elementary school. It’s a relatively easy instrument to begin with but requires as much work as any other instrument on a professional level. The one most commonly used in concerts is the F-tuned alto recorder.

Recorders are typically made of wood: cherry, pear tree, mapple. Concert recorders often usitilize hard Mediterranean box tree, grenadilla or ebony. According to Kimmo, the sonic differences between different wood materials are such that an ordinary listener face difficulties in hearing them but recorder players don’t. Important sonic variables are the brightness of the sound, the range of the sound, and the purity of the harmonics – the very same variables that speaker builders value in their designs.

A plenty of music has been composed for the recorder. The golden period lasted from renessaince to baroque, from the 16th century to the 18th century. Vivaldi and Telemann wrote music for the recorder but also eg. many Traverso-music was scored for the recorder in France. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos need a recorder, and so on. In addition, there is a good deal of solo flute music from the Baroque period, trio sonatas etc.

In the 19th century the recorder was largely forgotten and made a comeback only early 20th century. The so called Period Instrument Movement started up from the recorder and cembalo. Also, quite a lot of contemporary music has been written for the recorder.

The recorder differs from violins and cellos in that it doesn’t necessarily mature well. The recorder is continuously exposed to moisture caused by the breath of the player, which is why the properties of the instruments do not automatically get better over the time. In a good recorder the tolerances of eg. the mouth piece are really tight. Therefore reconstructions of old instruments often sound better than the originals, and that’s why eg. Delrin can be a very suitable material for building recorders.

What makes a good recorder recording?

Kimmo Absetz is a music teacher, an audiophile and expert in optics for bird watching. He’s currently giving music lessons eg. at the Helsinki Conservatory of Music, and teaching historical notation at Helsinki Polytechnic Stadia. Kimmo’s instrument is a recorder and other members of the same flute family.

In Kimmo’s mind ingredients of a good recorder recording are ”a right balance between the remoteness of church acoustics and the presence of studio recordings. If the reverberation time is too long, the player’s articulation becomes clouded as opposed eg. to what happens with a symphonic orchestra. Solo flute recordings naturally accept more reverberation.”

Furthermore, in good recordings playing a recorder succeeds also in terms of voicing. Odd as it may sound, some recorder players sound better than the others, and the reason lies in different physical properties inside their head, and one can hear that too.

The sound of a recorder contains many harmonics. In order to be able to enjoy recorder recordings, it is utterly important that the harmonics are reproduced right. Pronounced sibilants, hiss etc. can make a recording irritating.

Below is Kimmo’s Top 3 recorder CDs, two of them by Dan Laurin, one of the finest recorder players of today, with excellent techniques and deep musicianship. Michael Schneider is another Kimmo’s favourite. His playing is gaily virtuosic and energetic, and in slow movements oppressively beautiful. Choosing between good recordings depends also on the mood, Kimmo adds.

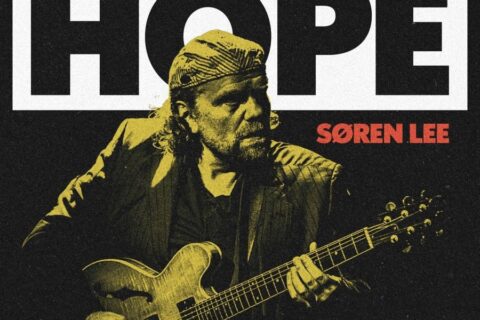

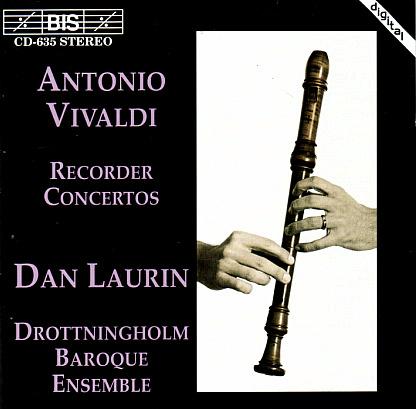

Antonio Vivaldi: Recorder Concertos, Dan Laurin, Drottningholm Baroque Ensemble, BIS CD-635.

A combination of a great Baroque Italian composer, some of his most beautiful compositions, and one of the finest rerorder players of our times. In addition to excellent techniques Dan Laurin possesses musicality thanks to which all the phrases come to live, the rhythm breaths naturally and nuanced, and improvised ornaments add true meaning to the music, not just as a product of imagination.

Recording itself is intimate with not much hall acoustics, which is why Laurin’s solutions are conveyed directly, and the balance between the soloist and the orchestra (often troublesome due to the recorder’s limited dynamics) is very good.

Jacob van Eyck: Der Fluyten Lust-hof (complete), Dan Laurin, recorder, BIS CD 775/780.

This is fairly extreme. With 143 tracks and nine CDs, this is rather a recommendation for true recorder enthusiasts. Van Eyck’s collection was published in 1649 and 1654. He was birth blind and “golden ear” who became famous as the best tuner of clockworks of his time. Moreover, he was a very talented recorder player, whose live concerts in Uttrecht have a legendary reputation.

This is fairly extreme. With 143 tracks and nine CDs, this is rather a recommendation for true recorder enthusiasts. Van Eyck’s collection was published in 1649 and 1654. He was birth blind and “golden ear” who became famous as the best tuner of clockworks of his time. Moreover, he was a very talented recorder player, whose live concerts in Uttrecht have a legendary reputation.

Der Fluyten Lust-hof is a collection of van Eyck’s popular pieces: dances, songs, psalms etc. into which he added improvised variations with ever faster tempos. Laurin’s playing is superb. The recording’s acoustics is quite sonorous but thanks to close miking all details come forward and Laurin’s expressive sound production is simple to follow. Laurin uses a wide selection of copies of recorder types from the 17th century.

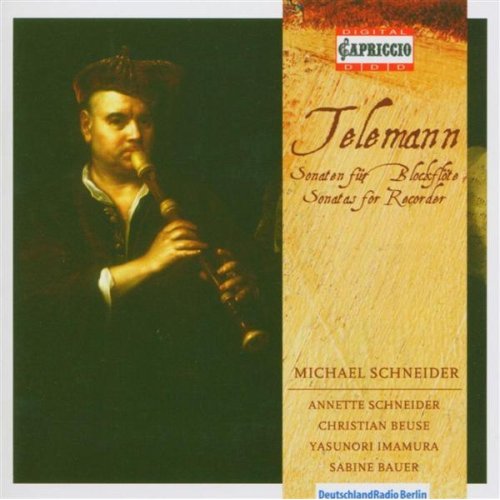

Telemann: Sonaten für Blockflöte, Michael Schneider, Blockflöte, Capriccio 67 070.

Nine sonatas and sonatines by one of Baroque’s most productive composer, who in his own time was more popular than Bachia and Handel. His works written for a recorder are wonderful, and Michael Schneider’s take is joyfully virtuosic and rocking but also oppressively beautiful in slow movements.

Schneider’s improvised ornaments are imaginative and abundant but also so successful that the music clearly benefits. Schneider’s playing is rich and solid, and intonation very sharp. The recording is a happy a compromise of natural acoustics and clarity, and tonally rich and exuberant.

More info: www.recorderhomepage.net. Under “recordings” is a search engine whose “recorded recorders” button gives specific info on numerous recorder recordings, incl. eg. those featuring van Eyck’s music.