There is no such a thing as Mozart’s Requiem. What exists is only a beginning for a work that a mysterious messanger ordered from Mozart. The Count Franz von Walsegg zu Stuppach’s wife Anna died only at the age of 20, and the Count wanted to honour the memory of his beloved wife. The whole operation had to be kept in secret since the Count wanted to give an impression that he himself had composed the requiem.

The fate of the Requiem is the ordinary: Mozart died before the work was finished. People remember Shaffer’s film ”Amadeus” from 1984, directed by Milos Forman: the cadaverous genius hardly has strength to lift up his arm until after eight bars or so from the beginning of Lacrimosa, says goodbye to the world.

Mozart’s wife Constanze gave the raw version of the Requiem, after having refused a couple of times, to Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who finalized the work in 1792. Who were the true finalizers is a still open question.

The catholic Requiem is named after the first words of the text: ”requiem aeternam dona eis”, ”give them an eternal rest”. After Mozart, Verdi, Berlioz, Fauré, Bruckner and Dvorák have been able compose a Requiem that have stood the test of time and remained in the standard repertoire. Brahms and Britten composed their modified Requiems. Memorable is also the Requiem of Einojuhani Rautavaara.

Mozart’s Requiem is one of the big hits of Western art/classic music, a top-ten classic. The man in the street would recognize Mozart’s Requeim especially from its Lacrimosa part that has been used, removed from the context, to evoke emotions, reaching the catharsis and additionally, in already pathetic connections, to sickening. Lacrimosa tears, a guilty person rises from the dust and will be condemned, and for whom people pray for clemency, sells well.

Nike has advertised Air Jordan XX2 basketball shoes with the help of Lacrimosa’s music. (In the Ad, the game is coming to an end, and final seconds are at hand. The visiting team is a point behind. The home team Wildcats and its supporters pray in despair when the visiting team gets the ball, and scores two points and wins the match. The head of the lion is on the floor, the player who made the winning score stays dead still.) In the Ad everything’s shown in slow motion. Mozart blogger Sherry L. Davies writes: ”Both the loosing team and Mozart run out of time. The player who made the decisive shot represents death. The team loses the game, Mozart everything.”

The flight company Finnair has made use of Mozart’s music (aria “Ruhe sanft” in the opera Zaide) in its advertisement using an identical “slow down” formula.

In films Lacrimosa is performed, alongside the picture, when the star actor/actress falls down the staircase (slowed down, of course!), when the wife dies, right after a kidnapping, when the archbishop is killed cruelly. The rock band Evanescense too is a friend of Lacrimosa.

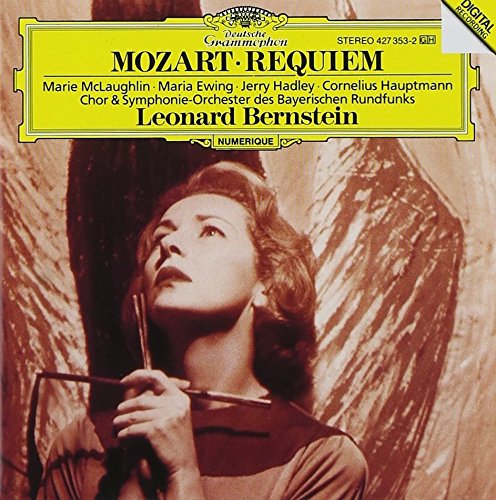

Lacrimosa slowed down, ”the true act” is well depicted and accomplished by Leonard Bernstein in his recording with Bayerischen Rundfunks orchestra from 1988. The duration of his Lacrimosa part is 5´38, over 2,5 minutes longer than what Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Concentus Musicus Wien in the 1982 recording could stand (time: 2´54). Was it really the same piece they were conducting?

Barenboim’s Lacrimosa (Orchestre de Paris) from 1985 spends 3´14, as does Solti’s Lacrimosa recorded in a concert that honoured Mozart’s 200 Anniversary (Wien philharmonics).

Two decades later Harnoncourt, in his 2003 recording (the same orchestera) leans toward Bernsteinin with 13 seconds (duration now: 3´07). Karajan’s Lacrimosa from 1986 with Wien philharmonics takes a second longer, 3´08.

Staring at the stopwatch is however pointless: to the listener credibility of the content is what matters. The snail of all Lacrimosas, Bernstein, makes his recording credible. The whole recording is much more interesting than the basic set of Barenboim. Introitus already tells about what’s coming, and the start is shockingly slow. The only minus point of the recording is the tenor Jerry Hadley, whose performance is colored by opera cliches, while the music itself is of course church music. Lacrimosa is the high point of Bernstein’s interpretation: the whole Requiem must be listened in relation to it. Mozart presumably composed some gems for the Offertorium part, but Lacrimosa’s first bars are what stay in the history.

Bernstein’s live recording holds the balance between the orchestra, choir and soloists fairly well, but is a tad too businesslike.

Karajan’s Requiem is as one would expect categorical, almost pushy, but its Lacrimosa is surprisingly correct. The recording suffers from the soprano Anna Tomowa-Sintow’s , who annoyingly slides into notes. The choir sounds congested in the background when Karajan add vibrato of his first violins. Barenboim in his recording has the best group of soloists: young Kathleen Battle is dazzling, Matti Salminen the best possible Mozart bass (the long breath in Tuba mirumin!), the tone colour of Ann Murray and David Rendall goes well with the foursome.

Barenboim’s rhythmic treatment is however lame, Rex is boring, Lacrimosa does not inspire. Crescendos are Barenboim’s strength. Technically the recording is fiasco: fuzzy, messy, devoid of mellowness and full of distorted brass instruments.

Barenboim’s rhythmic treatment is however lame, Rex is boring, Lacrimosa does not inspire. Crescendos are Barenboim’s strength. Technically the recording is fiasco: fuzzy, messy, devoid of mellowness and full of distorted brass instruments.

Solti’s four soloists form an uneven group but the tone itself is powerful, Confutatis a true cannon! The recording highlights St. Stephens’ vaults well.

Harnoncourt’s first version with original instruments and the fragility of pounding accents provide a challenge to the sound engineers. At the same time, the choir stands too far in the background.

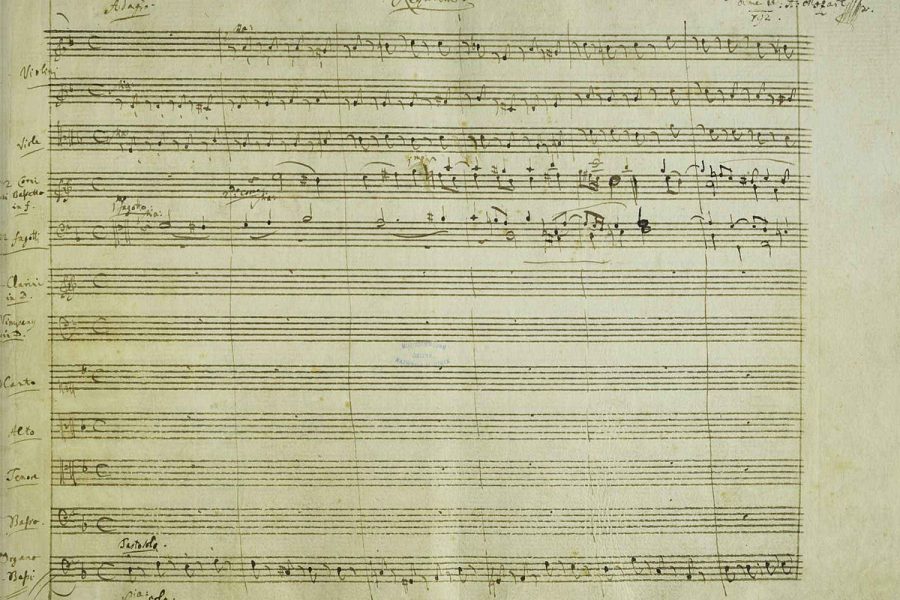

Out of the six recordings, number one is Harnoncourt and Concentus Musicus Wien, the later version. Lacrimosa in this recording is catchy, the complete opposite of Bernstein’s dragging version, but the dramatic impact is of high class. SACD sound is a big relief after so many muddy recordings, and brings the soloists forward naturally. A special treat is a CD-Rom track on Mozart’s original manuscript including the first eight bars of the Lacrimosa.

Here are the recordings:

1. Vienna Philharmonic, Wiener Singverein, Herbert von Karajan, DG 431 288-2 (1986)

2. Orchestre de Paris, Choeur de Paris, Daniel Barenboim, EMI 7 47342 2 (1985)

3. Vienna Philharmonic, Wiener Staatsopernchor, Georg Solti DECCA 436 607-2 (1991)

4. Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Leonard Bernstein, DG 427 353-2 (1988)

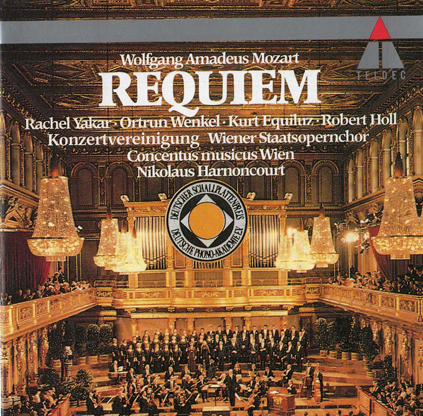

5. Concentus Musicus Wien, Wiener Staatsopernchor, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Teldec 2292-42911-2 (1982)

6. Concentus Musicus Wien, Arnold Schönberg Chor, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, DHM 82876 58705 2, SACD (2003)