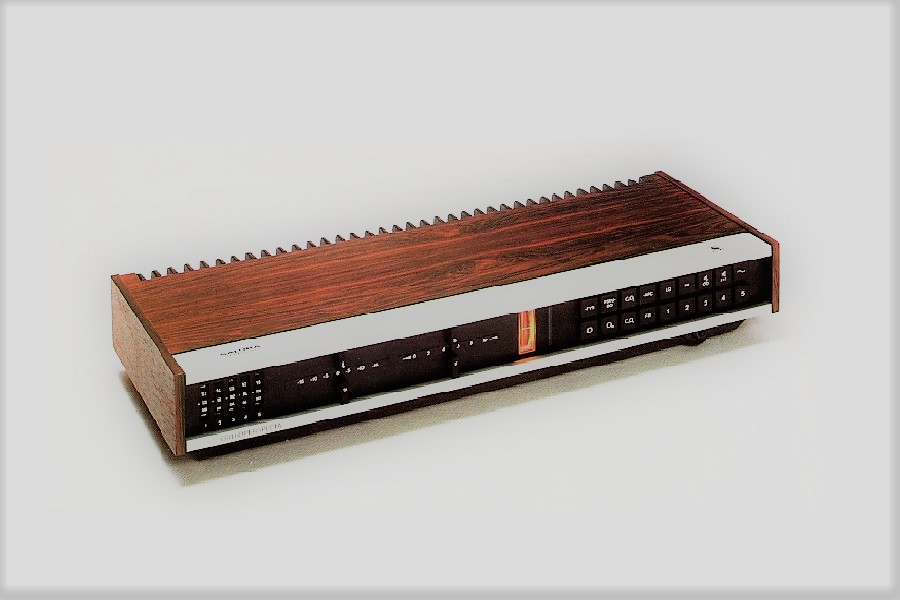

Compared to Voimaradio MS-3K (with a wooden chassis from the 1960s), OP-3 (several versions from the 70s) or Wattram Super Stereo (less than 100 copies were made in the beginning of the 80s), Salora 3000 receiver-amp (1972-76) is not particularly mind-blowing creation as an amplifier. It lacks the OP-3’s pre- and power stage’s contra-phase circuitry, tubes of the the OP-3 output stage, and all sorts of exciting solid state technology of the Wattram.

According to its brochure, Salora 3000 sports 53 transistors, of which two MSOFETs, two FETs and 49 bipolars. In addition, there are 22 diodes and three ICs. As to inputs, one’s for the MM phono and two line-level for a tape recorder and one for a microphone plus the headphone out. The very modern FM tuner was designed by Pertti Lampinen. The front panel features the volume, clever input selector, tone controls for the bass (50Hz +/-16dB) and treble (10kHz +/-14dB), five presets for radio channels and rumble/noise filters for vinyl records.

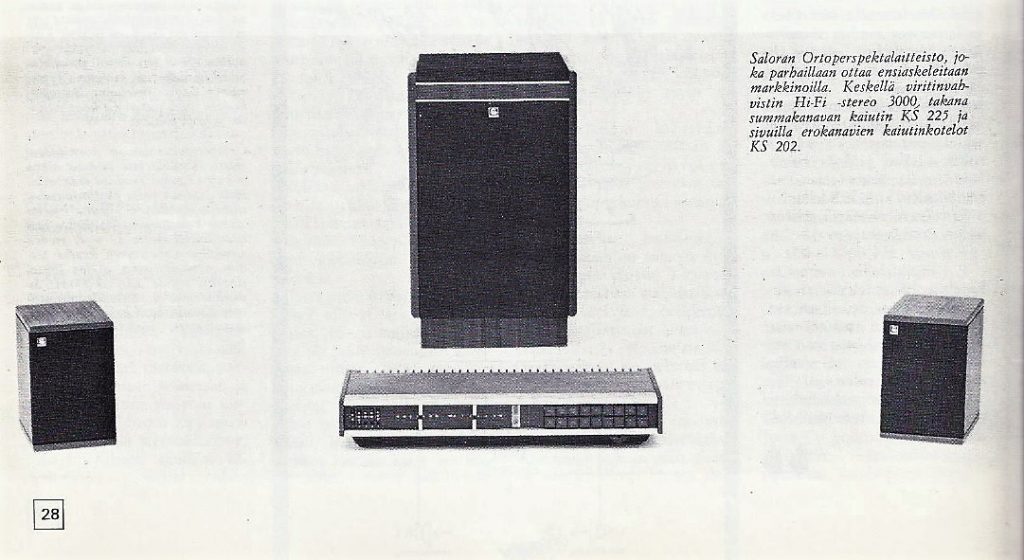

What really makes the Salora 3000 worth a closer acquaintance, is its three speaker terminals on the rear panel, one for the center channel speaker, and two for the side wall speakers. Speakers are part of the same package.

What we’re dealing with here is, of course, the Ortoperspekta sound reproduction system developed by the grand old man of the Finnish audio engineering, Mr Tapio Köykkä. For the 3000 OP, Salora made use of Köykkä’s patent with a lisence. The Salora 2000 was just an ordinary stereo-fm-receiver/amplifier, with basically the same power amp topology as in the 3000.

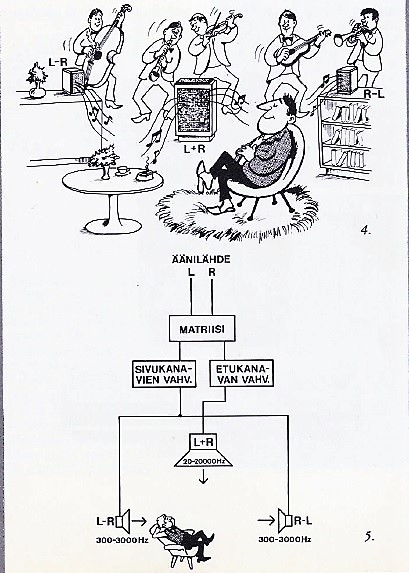

In simple terms, the idea of Ortoperspekta is to lead the sum M of the stereo signal (the sum of the original channels A+B) into the center speaker, while the side speakers would get the difference signal S in opposite phase (A-B/B-A). During the playback, the level of the sum (direct) and (reflected/diffused) difference signal can be adjusted with separate volume controls in order to adjusting the relative level of the difference channel for the optimal ”stereo” image. Think of it as a kind of ”three-channel” 1.2 –stereo system.

To understand how the system works in practice, it’s necessary to get a good grip of the reasons that resulted in this invention.

A concert – the holy grail

Wading through numerous articles and other siding documents, written by Mr Köykkä, there’s one matter that frequently hoppes on the eyes, even annoyingly often: the concert hall. The concert hall this, the concert hall that, the concert hall … , the concert hall … You get the point.

What is it about the concert hall that justifies such a fuss? Well, good music is often performed in a concert hall. That’s not a joke, but an important and well-grounded piece of background info. According to Köykkä’s grandson and other sources, Köykkä – ”inspired by the world success of the conductor Okko Kamu” – was exclusively listening to classic music, and specifically the sort of classic music that is performed in a concert hall, symphonic works and other orchestral pieces as a prime example. He is known to have been personally in good terms and closely associated with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra.

It would perhaps be too much to claim that Köykkä designed the OP system for himself, but it is clear than daylight that the music he preferred, and the way in which he preferred to listen to his music, strongly speaks for his invention. Or what do you make of the following?

”Of all the possibilities that the stereo is able to bestow, the most enjoyable and the most precious one is the impression of being in a concert hall, the acoustic perspective that is often not achieved with the ”old stereo”.” The ”old stereo” was the term Köykkä often applied to the traditional 2-channel stereo reproduction.

In other words, he was dreaming that the listener could have the emmersive feeling of sitting in a large concert hall, ideally in the same one where the performance was recorded, ”no matter how small the listening room is actually”.

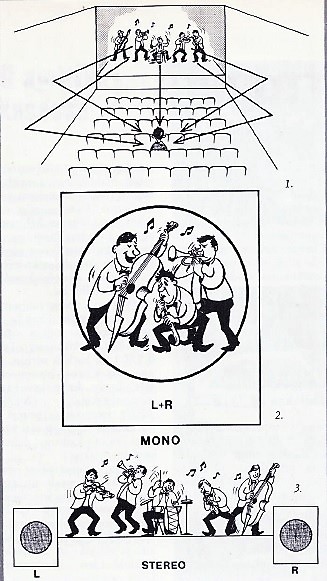

In the concert hall, an enlightened music enthusiast would never sit, this is Köykkä’s firm opinion, on the front bench but in the middle of the auditorium (that’s what HiFi hobbyists would call the ”sweet spot”, ie. the best seats). In the front of the concert hall, the concert goer is able to accurately track direction and location of different instruments, but the “perspective” of the sound in the best seats, more than compensates for the loss of the (spatial) precision! Now we’re getting to the point!

The acoustic perspective

The acoustic perspective or the impression of it, that Köykkä so dearly glorifies is created when the air (space, medium) between the orchestra and the audience moves /transfers information, vibrations, to the listener’s ears through two channels that are not left and right, but longitudinal and transversea (sideways). Out of the coalescence of these two types of vibrations is the acoustics of a concert hall born.

Köykkä was convinced that these two channels, the longitudinal and the transversea, are able to transmit to the listener ”all possible vibrational directions” of the sound.

The longitudinal channel transmits the instruments’ direct and in phase sound, and the transverse channel echoy or reflected sounds from the side. It is the role of the latter in the process that is central: “the task of the reflected sounds is to transmit to the listener information on the mutual distance between the sound sources, their separateness.”

Space, distance, seprateness. These are all different things to Köykkä (eg. by ”space” he means the impression of the size of the concert hall), and these are sensed with the help of time and phase differences of the reflected sounds, relative to the direct sound.

Modern hifi hobbyists often talk about transparency of the sound meaning ”resolution”, ”richness of nuances” etc. Köykkä instead talks about ”transparency” (”Durchsichtigkeit”) in the right sense of the word, namely as the concreteness of the soundstage, which manifests itself, for example, in the feeling of “distinctiveness of the sound sources or intruments”. That is, transparency is a property of the sound stage, not of a sound in general.

As the angle of arrival of the sound decreases, the stereo effect is reduced toward the back of the concert hall, and the reflected sounds further reduce the accuracy of the perception of the sound’s direction. Eventually, the sound becomes monophonic. Since such a “monaural” sound is better than stereo in a concert hall, why not at home?, Köykkä wonders.

He however denies that the sound further away in the hall would be ”pure mono” or even pseudo-stereo. His point is that the ”ping-pong-stereo” is replaced by ”the sense of space sensed with two ears, with the sense of distance, and impression that the instruments are distinct from each other”. That is, the ”perspective stereo”.

Hifi hobbyists of today may not buy Köykkä’s bold claim that with the left-right stereo ”the listener is unable to form an impression of the space and the depth of the concert hall”. Köykkä, however, is serious and unconditional about this: there’s no way one and the same person can sit in the front row and at the back of the hall at the same time. So it’s either take it or leave it.

”Two channel directonality is no prerequisite whatsoever for a perspective impression”, says Köykkä. Far more essential is how to transfer the concert hall’s right acoustic perspective to the listening room at home?

The tactics of two holes

The tactics of two holes

If the sound, as it appears in the best places of the concert hall, would be auditioned from inside a room with two holes on one wall, to mark two microphones or two loudspeakers, and the left L is lead to one hole, and the right R to the other, as in the ”old stereo”, there won’t be, according to Köykkä, no right (stereophonic) acoustic image or impression of the perspective of the sound.

This is because, with the old 2-channel stereo, the impression of the direction of the sound is thought to arise solely on the basis of the time differences of the upcoming sounds, and reflections from the side walls are not properly represented. The old stereo (based on the directional impression) tends to transmit only the direct sound of the recording space leaving out the recording space’s transverse reflected sounds, so important for creating the right perspective.

In the old stereo, two loudspeakers are longitudinal radiators reproducing the direct sound (M-information) of the recording space in phase directly forward as one unified wall of audio wave. That applies to channel separation too conveying the out-of-phase info, and hence the stereo image (ie. stereo separation); in the old stereo the image is moving as a result of the co-effect of the pressure waves generated by the loudspeakers as a rapidly absorbing transverse sound wave toward the listener. The reflected out-of-phase sounds (S-information) are “acoustically submerged under the direct sound” and are therefore subdued or not audible at all.

Furthermore, these weak sounds come from a wrong direction, that is, from the front, and not from the sides as they should. In other words, the old stereo doesn’t reproduce the instruments’ phase clues and differences in a correct way.

And as all hifi hobbyists well know, in order to hear the weak difference signals (transverse vibrations where the listener sits) the friend of the old stereo needs to sit precisely in the middle of the loudspeakers, and the room needs to be perfectly correctly acousticated, not too much, nor too little.

This two-speaker stereo, which current listening practices are still largely based on, was for Köykkä a “technical gimmic”, in which the ”presence of the speakers” and the ”mechanical nature of listening” are emphasized. Köykkä couldn’t understand that anybody would want the ”direction-stereo”s trump card: the ping-pong effect, in particular because there won’t be the ping-pong effect unless the sound sources (loudspeakers) are exactly in the right place, the listener exactly in the middle of the speakers, the two channels exactly aligned and levelled, and the listener not moving his head not even by 1 cm. Otherwise, “the speakers would be exposed”.

Although the problems of the 2-channel stereo are partly caused by the fact that ”speakers emit sound that is fundamentally meant for headphones”, Köykkä didn’t believe that the binaural stereo, in which the cross talk of the channels is prevented, would bring much improvement over traditional stereo. ”Natural sound transmission techniques requires blending/mixing the channels.” The big question is: How?

Three holes it must be

Three holes it must be

Köykkä’s proposal is that the M-info (the sound coming directly and in phase from the instruments to the microphone) is fed to a loudspeaker that is in front of the listener (think of a center speaker in a modern home theater system), and the S-info, the reflected sounds (the difference signals) into two smaller loudspeaker on the side walls out of phase. The sound is now coming to the room from three holes: one in front and one on each of the side walls. In Köykkä’s mind this tactics of three holes would be the most effective way to transform the old-style stereo image into one with a natural perspective, and thus to obtain a true spatial impression of the concert hall with the sense of mutual distance and separateness of the instruments.

With the three holes, the sound sources that appear in the middle (of the stage) are reproduced from the middle, as they should. The source on the right hand side is reproduced in phase from the right wall speaker, and out of phase from the left wall speaker (in Salora OP, this is taken care electronically by connecting one of the side speakers to the DIN on the right hand’s side, and the other speaker to the DIN on the left). This way the listener gets an impression that the source situates right from the center speaker, but unlike in the 2-ch old stereo, ”the movement of the source to the right is not as clear or sharp and exaggerated but perspective …”: the instruments to the right are reproduced as if coming further away behind the center speaker.

If two instruments are sounding at different times, they will be heard from the same “somewhere” (vague direction). If the same instruments are playing simultaneously, they seem to come from different places, but not sidewise (L and R) as in the old stereo! With the three hole stereo, the left-right stereo is transformed into near-distant stereo.

Thus the core idea of the three-hole perspective stereo is to extract the echoes and reflected sounds (the difference signal of the microphones) from the direct sound, and to amplify them appropriately so that with regard to the natural spatial effect, they are rightly proportional to the direct sound. The inadequate presence of reflected sounds, ie. the transversal vibrations of the concert hall, was the single most annoying factor for Köykkä in the binocular stereo, and motivated him to develop his own perspective stereo.

“Transverse information, the vibrations, on standard stereo discs are so weak that it’s almost impossible to get enough of them on a regular stereo.”

In order for the reflected sounds to really be audible (so that ear would discern them), they must not only be reproduced strongly enough, but also from a different direction than the direct sound, just like in the concert hall. An even clearer distinctiveness of the instruments is achieved if the fundaments of the musical instruments are played back in phase, but on higher harmonics more and more out of phase. One of the defects of the old stereophonia is that notes of all frequencies are reproduced more or less in phase.

The perspective stereo

So conditions for a true perspective audio are met in a tri-spot stereo, which Köykkä christened Ortoperspekta. The right level of the side speakers, reproducing reflected sounds, can be adjusted with a separate amplifier (inside the receiver) and own volume control. In addition, the reflected sounds are, as they should, in the opposite phase in the left and right side speakers. The frequency response of the side speakers is limited to 300-5000 Hz while the center speaker plays back the entire band.

In Ortoperspekta, the listener does not have to be in the middle of the speakers because the stereo effect is similar over a wide listening area. Moreover, the sound also retains its stereophonicity (stereo info is audible) when quietly listening. It’s easier to reduce the level of noise harmful to hearing the S information. Also, there’s no “fake separation” problem of the old stereo (a strong transverse resonance in the room, so called standing wave, at frequencies where the distance between the speakers is the same as the wavelength or its multiple, occurs).

Back to earth

Like all great theoreticians Köykkä idealizes and sees the world black and white. Köykkä also lived long enough to see that despite the promising beginning, the world didn’t conform into his ingenious ideas. And the reason is not hard to see.

By building his system firmly around the music of a concert hall, and ignoring all those for whom listening to symphonic music in a concert hall does not represent the highest and most subleme level of music listening, he right off made Ortoperspekta irrelevant to over 95% of music lovers. And the figure is growing if we count in those informed concert goers who nevertheless prefer to listen to their admired soloist (cellist, soprano, etc.) ”wrongly” from a close distance without letting their listening pleasure tail off.

An even bigger problem for Köykkä are the recordings. Only a fraction of them is recorded in a way that best serves listening to music through his perspective stereo, ie. in a way that the reflected sounds of the concert hall would have been sufficiently captured on the tape.

From the standpoint of the Ortoperspekta, the best recordings are those recorded with the MS technology, i.e. with two microphones, one of which, a sensitive cardioid, is on axis, and the other, so called figure eight mic, is crosswise to the center axis. XY recordings, where two condensation microphones are crossed at a 90-120 degree angle, are also worthwhile.

The thing is that MS- or XY- recordings are fairly rare even among classic music albums (many instruments being recorded separately near field and then later mixed in), and studio productions are almost without exception recorded in some other way than MS/XY, and often afterwards adding artificial space/echo.

DIY MS tapes

Köykkä couldn’t care less. He only had about two dozens of LPs in “active listening” (according to his grandson). Instead, he was a big friend of FM radio that broadcasted plenty of classic and other serious acoustic music at the time.

With the Ortoperspekta system mono broadcasts can be listened to as pseudo-stereo (artificial S- information fed to the S- channel) , and stereo broadcasts in the MS format. With the Köykkä OP3 amplifier it was convenient to make MS tapes from the radio stereo broadcasts, and this is exactly what Köykkä did and believed should be done. He had a long row of MS tapes for his own use in his bookshelf.

Neither did Köykkä see a big problem if his perspective stereo was used for listening to ordinary stereo recordings. For this, one just had to make sure that the side speakers are symmetrically positioned at the distance of 1.5m from the center speaker, and the listener is exactly in the middle (same distance) from the loudspeakers. If so, according to Köykkä, the right sense of distance and space are lost, but it wouldn’t prevent anybody from listening to standard stereo!

Regardless of the microphone recording mode, all recordings when played back with the Ortoperspekta system, go through the same M and S channel (L-R) transformation process, where L and R are for the most part the same M information, and S very weak. S (as well as M) is separately taken out and amplified in the MS matrix in order to give it a better presentation relative to the M information.

But how the outcome will be with recordings that are recorded with some other than MS/XY microphone techniques, is the key issue. It’s a question of life or death, when the suitability of Salora 3000 amplifier is assessed for today’s music listening. If the Ortoperspekta system were to function as intended only on “their own” discs, the Salora 3000 as well as all Köykkä’s own Voimaradio amplifiers could be put in the marging as anachronistic. Fortunately, that’s not quite as simple as that.

As far as I know, only once Köykkä admitted that ordinary stereo could sound better with ”wrongly” recorded stereo recordings.

Ortoperspekta

In theory the Ortoperspekta or the perspective stereo could be carried out without a dedicated amplifier with three loudspeakers. This would require that the volume of the side speakers could be adjusted within sufficiently wide limits, which is difficult to implement in practice. Therefore, in the Ortoperspekta, the new channels, the M-sum-channel and the S-separation-channel, are generated electrically by means of the preamplifier’s MS matrix.

The MS matrix of Salora 3000 is princpally similar to the one in Köykkä’s own Voima OP-3 or Wattram, which included both tubed and transistorized versions during time.

Thanks to its electronic implementation, the difference-amplifier (amplifier that drives the side speakers) can be less powerful (10W in Salora 3000) and simpler than the main channel amplifier (30-40W in Salora 3000). Actually, the topology and driver circuitry, as well as the supply voltage in both amps are the same but marginally cheaper power lower current transistors can be utilized in the S-channel output, due to series connected speakers with higher ohmic load. The advantage of electronic implementation is also that the system is always symmetrical and balanced regardless of the room acoustics.

Because the sounds, whose wavelength is much greater than the distance between human ears, are not heard from any particular direction but are A-B = 0 independently of the input direction, the bass frequencies (less than 300Hz) are played back with only one speaker. According to Köykkä, only one such mono speaker should be used to achieve a smooth bass performance.

On the other hand, the lowest frequency that would cause any sound coming out of the side speakers is about 300Hz. Therefore, the lower end of the frequency response of the side loudspeakers is limited to 300Hz. This also prevents the turntable rumble from being reproduced from the side speakers. When the side speakers do not need a woofer, they do not have to be very large.

They do not even need a tweeter because the appearance of perspective stereo image does not depend on hearing the highest frequencies. For this reason, the bandwidth of both side speakers in both the Salora 3000 and Voimaradio systems has been cut off above 5 kHz reducing also distortion and noise.

Salora 3000 loudspeakers

In the Voimaradio OP-3 system, the mono speaker was a one-way design with two Goodmans Twinaxiom full-range speaker units without a separate tweeter and no crossover. The 19x19cm side speakers hid widebandwidth drivers.

Salora developed a range of new loudspeakers for its own amplifier series. For the Ortoperspekta models, the KS225 speaker was recommended as the center speaker and the KS 202 for the sides. The KS 225 front panel features a 4-inch paper-cone mid-range element and a hard plastic dome tweeter smaller than an inch. On top of the cabinet is a 10-inch woofer in a sealed cabinet shooting sound directly to the ceiling. All the components of the crossover were from ITT. The KS 202 had a 4-inch mid-range element and a small tweeter.

I’ve heard the original Köykkä loudspeakers, and I would have loved to have those for this ”test”. On the other hand, I do not think other speakers would have changed my listening impressions essentially: the Salora loudspeakers did what they were expected do as part of a perspective stereo system, and the mono loudspeaker was surprisingly good-sounding even though it would most certainly be judged as ”nothing special” by modern standards.

Regarding speaker placement, Köykkä’s instructions are quite plain. The mono speaker he advices to place on the floor near the corner (to obtain more bass?), not toward the listener. As to the side speakers, both should be 3-6m from the main speaker, not toward the listener, and not necessarily at the same distance or height. “It is an advantage that they are at a different height,” Köykkä claims.

”In grandpa’s listening room in Sipoonkatu (a street in Helsinki) the speakers were mainly ‘here and there’. The main speaker was often underneath of the couch, and if needed Köykkä dragged up the side speakers in the book shelf a bit forward”, the grandson memorises.

I begun my listenings with the Salora 3000 main speaker directly in front of me at the distance about 3 meters (between two standard stereo speakers), the side speakers vaguely on my right and lef hand side roughly 2-3 meters away and at a slightly different height.

First I set the volume of the main speaker to fit the record at hand, then adjusted the volume of the side speakers so that I couldn’t quite distinguish their sound from the sound of the main speaker. The volume is right when the spatial effect, the perspective, that Köykkä so dearly speaks of, is obvious. The idea of the volume adjustment is quickly learned.

Then I just put records on the platter (mainly CDs), and listened to the Salora 3000 OP system, and a ”normal” stereo system (Electrovoice Patricians or German widebandwidth speakers driven by small power tube amplifiers) in rotation. I used BIS symphony orchestra recordings to mimic true MS-type recordings. Otherwise I played albums and music of all kinds: orchestral music, chamber music, solo music, all-studio outputs, electronic rhythm music, compilation CDs by speaker manufacturers, etc.

Listening to three holes

From the first notes it was obvious that the so-called “stereo image” of the Ortoperspekta system is very unlike the one of the traditional stereo. It takes some time for the ear to get used to it, especially to the share of the sound coming directly from the the front speaker, but soon the listener takes up the threads. At best, the feeling of space (the spatial image) makes one hooked. It’s a great feeling when the side speakers disappear somewhere in the air and music floats intangibly. From time to time, I had to stand up and go and check that there really was sound coming from the side speakers.

I soon realized that the most important aspect in the Ortoperspekta’s spatial performance was not whether it was able to convey the concert hall’s acoustics at home or not, (which I do not personally care too much anyway), but the ease of listening that it brough about. A direct comparison with the traditional two-hole stereo showed the well-known fact how tiresome and stressful for the brain the traditional stereo can be, especially during long listening sessions, how much the brain needs to work to continuosly adapt to the stereo information even though we’re deliberately ignoring it when listening to music.

As Köykkä predicted, the 3-hole stereo will prove what price the brain pays for stereophonic ping-pong effect. With the Ortoperspekta system, stress was the last thing to come to mind. The listener sits down where he wants, and starts listening. Music flows from somewhere, from an unspecified direction, but in a very clear and comprehensible form. In my mind, to achieve the same ease of listening, the stereo speakers must be listened to partly sideways, as I often do, and well behind the stereo triangle, so that the sound becomes more monophonic. With the right recordings, the OP system provides even greater ease.

The OP sound is not mono, but thanks to the direct sum sound, it’s “monophonic”, side speakers transmitting only spatial info. This feature has two sides. On the one hand, there is many music/recordings (solo instruments, piano, vocals) that, compared to the traditional stereo, benefit from the monophonic kind of sound, ie. that the main sound source (instrument, voice) pronouncedly comes from the center.

In fact, listening to Ortoperspekta encourages to experiment with one speaker between the two stereo speakers radiating the same amount of left and right channels (L + R). Köykkä would not like this as the arrangement only strengthens the direct sound that there already is too much. But I am sure that there are recordings with which it works.

Then again, there are recordings, such as some closely taped orchestral recordings, string quartets, piano trios, etc., when the OP system concentrates too much audio material on the center channel/speaker. The sound becomes congested, too narrow and no help coming from the sides as it should. Compressing the sound to the center is an obvious defect of the OP system, not just with a few, but with quite a many recordings.

Another obvious inconvenience is that for all recordings the “intangibility” of the sound – “being nowhere” – does not suit equally well. There are albums with which the ”perspective stereo” sounds just obscure, and that’s not a good thing. In comparison, the traditional stereo effect is drier, but also deeper in a clearer way. The two-hole stereo opens up in front of the listener a Panorama what to admire, the OP opens up a big breathing space, but does not offer any clear, concrete object for admiration. Often the OP sounds as if one were listening to a concert in a church at the front door.

Naturally, there were recordings for which this unspecified “out there” is very well suited. Unsurprisingly these are typically minimalist recordings taped with two microphones and from a certain distance.

This starts to be boring on one hand/on the other hand talk. At first I expected I could tell more specifically what kind of recordings go well with the OP system and what not, but then it turned out to be impossible. The number of different options is simply too great. The way in which the success of the OP system depends on the choice of recordings is not a straightforward matter.

To find out, I chose two compilation CDs, one with classical music only, the other mostly non-classical, and went through them track by track. It often happened that when the expectation was that the OP would work fine, it didn’t, and when I least expected it, it worked surprisingly well. Often the traditional 2-hole stereo and the OP system gave quite an equal performance despite their differences.

If in the genre of classical music it was possible to do some sort of classification between the tracks (eg. the recordings of smaller combos sounded less favorable than the ones by bigger ones), the variation of the non-classical studio recording tracks was greater. For example, albums with artificial echo and spacing could sound pretty enjoyable with the OP system: the system made the artificial echo more natural sounding, as it were. But not always.

It was very difficult to anticipate how the OP system would function in practice. Clearly it was not the case that multi-microphoned and ”wrongly” mixed studio recordings could not work with the OP. In the same spirit it must be said that many such albums, which against expectations fared well in the the OP’s MS-matrix, worked fine with the traditional stereo too, often even better. And also in the opposite direction: an album that on the paper should sound good with the OP – and did so, sounded good even with the old stereo.

Ortoperspekta vs. Ambiofonics

How does the OP compare to multichannel systems, 5.1 or other? I don’t know, I do not own a home theater. It is, however, clear that Köykkä saw his system, quite rightly so, despite of its ”three” channels (two electric channels), stereofonic, only as a perspective one. It is also known that he did not make too much of the contemporary four-channel and other multi-track experiments. But it may well be that modern multi-channel AV system would have been to his liking.

Also, he did not support the idea of adding to the Ortoperspekta the main speakers of the old stereo, even though in the Wattram amp he gave such a possibility for the user. Köykkä simply did not believe the additional speakers would bring any improvement to the OP sound but only bring back the faults of the old stereo main speakers.

Nor was he too enthusiastic about the Finnish Ambiofonics system introduced by Unto V. Somerikko in 1964. In addition to the two stereo main speakers, the Ambiofonics sports two side or rear speakers, to which are fed the difference signal of the channels. This can be done by simply plugging the additional loudspeakers into the plus poles of the loudspeaker terminal. According to Köykkä, the Ambiofonics system does “improve the stereo effect of the old stereo, but also maintains its most significant shortcomings: the sound source in the middle (eg. singer) are heard from two speakers, unless the listener is exactly in the middle, false transverse vibrations weaken the stereo image, and the side speakers behind the listener are unnatural. ”

However, I did compare the OP’s perspective stereo to the sound of Ambiofonics, and the result was not as horrible as Köykkä portrays. Remember, by “stereo image” Köykkä didn’t not mean the accurate left-right separation of the sound sources, but the right or natural sense of distance and the distinctiveness of the instruments, ie. more vague spatial presentation. It was to this direction that the Ambiofonics took the sound. Since it is so easy, why not try it yourself. Note that all amps do not make the connection possible depending on the loudspeakers; make sure you know what you’re doing.

Conclusion

The contest between the old stereo and the Ortoperspekta perspective stereo was like choosing between two candies, different ones but candies anyway. Both systems have indisputable advantages when evaluated in the light of different music, and various recordings. The demarcation lines between different styles and fields of music, or the methods of recording, were not as sharp as I imagined beforehand, but they were there.

It is clear that there are recordings that do not sound particularly rational with the OP system. On the other hand, there are recordings and music listening options with which the OP sounds anything but a product of its time, very modern even.

In other respects too, Köykkä would be a timely figure in today’s sound reproduction circles, Hi-Fi. I’m thinking of the way in which he stressed the importance of the sound sources and belittled the significance of the loudspeakers, the fact that he was a friend of crossoverless single-drive widebandwidth speakers (or only a capacitively coupled assisting tweeter with 6dB/octave slope) decades before the current trend, how he emphasized the importance of transient playback and time coherence at the expence of the frequency response, and how he argued strongly for tube amplifiers at a time when all others were going for transistor amplifiers. In other words, he was a very far-sighted person, and is still topical.

The grandson Mikko Köykkä remembers how his grandpa “when the music critic Seppo Heikinheimo, multi-artist M.A. Numminen and other important fellows came to Köykkä’s home, kids were sent away from the listening room, and the men left there to talk for hours about music and sound ”

Even his grandma, Köykkä’s wife, was quite a person. When Mikko once was listening to his music, she came and commented: “Don’t listen to music at so quiet level, listen louder. That’s pointless listening! ”